Bahujan India is the Real Young India

- anand kshirsagar

- Aug 17, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent announcement of a historic tariff hike on China and various nations not only surprised the American business community but also sent shockwaves through the global value chain. Today, industries ranging from pin-making to shipbuilding rely heavily on Chinese manufacturing and skilled labor. In response, global firms are urgently seeking alternative production and labor sources as part of a 'China Plus One' strategy. Amid this disruption, many trade and economic scholars—both in India and abroad—are evaluating India’s potential, with its youthful workforce, as a natural contender for driving the next phase of global growth and prosperity.

Young India’s perceived potential as ‘Growth Market’ and ‘World’s factory’

India, the world’s most populous country with over 1.4 billion people, boasts a demographic advantage—more than 60% of its population is under the age of 35. Economists, policymakers, and business leaders increasingly view this youthful population as India's greatest asset, especially as countries like the U.S, Europe, China, and Japan confront rapidly aging populations. In a world growing older, India’s 600 million-strong young workforce holds immense potential to drive both domestic and global economic growth. Fueled by this demographic dividend, India is well-positioned to become a dynamic global producer of goods and services. This promise of a ‘Young India’ is drawing strong interest from global businesses and policymakers seeking new hubs for manufacturing and participation in India based value chains system.

‘Bahujan’ nature of ‘Young India’

While the prevailing policy narrative presents a ‘helicopter view’ of India’s youthful potential, this portrayal is misleadingly simplistic. It overlooks the complex social, economic, and cultural realities shaping India’s young population—particularly the Bahujan majority, comprising historically marginalized caste communities across all religions, including Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), De-Notified Tribes (D-NT) and Nomadic Tribes (NTs). These communities have long been the backbone of India’s productive labor force and continue to dominate the informal sectors like manufacturing, service, and agricultural sectors. According to the 1931 caste census and 2011 National Census, Bahujan communities constitute more than half of India’s population. In truth, India’s so-called demographic dividend is largely a Bahujan demographic dividend.

However, much of the policy discourse in India remains ‘socially sanitized’ and caste-blind, failing to account for the caste based structural exclusions these communities face. By ignoring the specific socio-economic makeup of this majority, scholars and experts risk underestimating both the challenges and the transformative potential of India’s demographic advantage. Despite their central role in the economy, Bahujan communities remain systematically excluded from access to quality education, healthcare, skill development, and wealth-building opportunities due to entrenched caste-based inequality When comparing India’s human development potential with that of China—its closest demographic counterpart—this contradiction becomes stark: the same youth celebrated as India’s economic future also belong to communities persistently denied the foundations of upward mobility. For international policymakers, investors, and development strategists, recognizing this tension is essential to understanding India’s true demographic reality.

Indian ‘Demographic Dividend’- Race against time

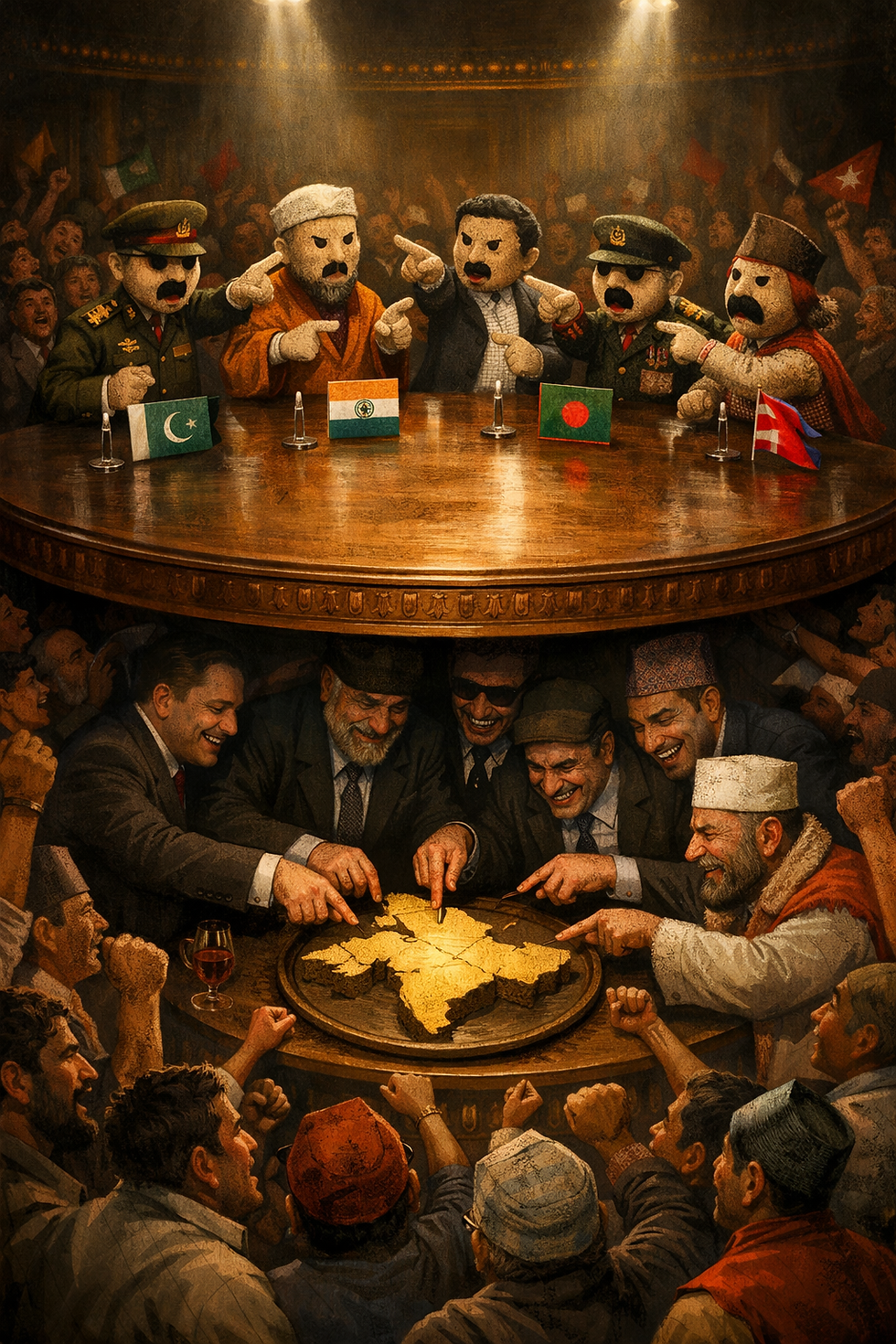

Time-bound investment in the human development of India’s majority Bahujan population can serve as a powerful engine for national wealth creation and a stable foundation for global trade and markets, yielding multigenerational benefits. However, India’s demographic dividend is a time-sensitive opportunity. Historical examples, such as post-WWII America’s ‘Baby Boomer Generation’, show that a young population advantage can eventually turn into a demographic liability. India faces a similar risk if the socially, educationally, and economically underdeveloped Bahujan youth remain neglected. Without holistic human development of Bahujan masses—India risks transforming into an ageing nation burdened with an unhealthy, uneducated, unskilled, and unemployed swath of people. This scenario could lead to severe domestic instability with wider geopolitical repercussions across South Asia and the Indo-Pacific, given India’s global diaspora, regional ties, and growing strategic influence. Recognizing the demographic dividend as a ‘Bahujan dividend’ and making strategic, long-term investments in Bahujan human development is essential to securing India’s future—and that of the world.

India amidst the Changing nature of the Global labor and value chain relationship

The evolving global economic, trade, and investment landscape demands fresh thinking in both India and the world. As the U.S. adopts aggressive tariff policies against China, investors and multinationals are actively diversifying their supply chains—a shift known as the “China Plus One” strategy—to minimize value chain disruptions. India stands at a cross roads of this shift, with its vast labor pool and growing consumer market. However, this potential will remain unrealized unless India centers its development strategy on the inclusion of its Bahujan workforce and consumer base. Without time bound Bahujan centric development policies, the China Plus One opportunity may only reinforce existing inequalities in India. Furthermore, with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning increasingly automating routine jobs in manufacturing and services, the creation and sustenance of high value creating jobs will depend on sustained, high-quality investments in education, healthcare, skills, and entrepreneurship for the Bahujan masses engaged in the informal and casual labour economy. Only then, can India fully leverage this geopolitical moment for equitable and sustainable growth.

Indian Politics and Bahujan community

The structure and function of the Indian caste system continue to shape everyday life across the country. Even today, caste influences key elements of the Indian economic life, such as the division of labor, access to livelihood opportunities, labor force participation, and the distribution of surplus value. Caste relations remain central to Indian politics from the local to the national level. Yet, mainstream political discourse—particularly at the state and national levels—is dominated by the perspectives and interests of upper-caste elites. These dominant political narratives often reduce caste-based social and economic inequalities to mere ‘economic disparities’ or ‘regional developmental imbalances’. As a result, they pursue populist welfare programs, state subsidies, and technocratic policy solutions that lack grounding in the lived realities of caste discrimination faced by the Bahujan majority.

When mainstream political parties engage with Bahujan issues, they often do so by fostering long-term dependency on upper-caste-dominated institutions, rather than empowering autonomous Bahujan leadership. Independent Bahujan social, political, and cultural voices are frequently delegitimized through token representation—party cadres from Bahujan communities who remain loyal to the political agendas of upper-caste leadership. This not only preconditions the policy narrative surrounding Bahujans but also deprives them of the ability to independently theorize and shape the foundational discourse on politics, economics, society, and culture in India.

Despite inclusive-sounding slogans such as Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas (Development for All, Cooperation of All) by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Sarvodaya (Upliftment of All) by M.K. Gandhi, Garibi Hatao (Eradicate Poverty) by Indira Gandhi, or Antyodaya (Empowerment of the Last Person) by Deen Dayal Upadhyay, systemic caste barriers remain entrenched. Bahujan communities continue to be severely underrepresented in higher education, media, corporate, and the tech industry, revealing the limited impact of these populist promises. While post-independence planned development and post-1990s liberalization have benefitted certain sections of society, they have deepened inequality and exclusion for many Bahujans, contributing to India’s growing income inequality.

India’s economic reforms have largely ignored caste realities, operating under the economic assumption that “a rising tide lifts all boats.” However, for many Bahujans, access to the boat itself was never granted. Today, India must reimagine development not as trickle-down growth but as structural transformation—anchored in the rights, needs, and aspirations of the Bahujan majority, particularly its younger demographic. This transformation requires a unified national political movement centered on Bahujan empowerment across social, economic, educational, and cultural domains.

Critics may claim that such a Bahujan-centric development agenda is socially divisive. This is a false binary. Inclusive development does not undermine upper-caste or elite interests—it expands opportunities for all. Empowering Bahujans will grow domestic markets, boost aggregate demand, strengthen the middle class, and enhance national productivity and cohesion. The prosperity of Bahujans is not a zero-sum outcome; it is the key to India’s shared and sustainable future.

Conclusion

Today, Bahujan community in India is not a marginal constituency. It is the beating heart of the young nation’s economical activity, cultural vitality, political stability and creation of the prosperity. Any reimagination of the global future and India’s role in it has to incorporate the central role of the Bahujan population. Ignoring such substantial part of global humanity is not just morally indefensible—it is economically shortsighted for the India and the world at large.

India’s future—and much of the world’s economic stability—hinges on whether the Bahujan majority is seen as a problem to be managed or as the solution to a more just, prosperous global order. We must choose the latter. The time to act is now. Recognising true nature of the Young India which is ‘Bahujan India’ is not just a national obligation for India—it is a strategic imperative for the world. ‘Bahujan India’ is the real ‘Young India’.

Comments