'Koyta' (Machete) Gangs of Pune City: Symptom of Larger Systemic Urban Crisis

- anand kshirsagar

- Jan 7

- 11 min read

Growing up as a Bahujan teenager in the 1990s, deprived, crime-infested slums and public housing projects in Yerwada, Pune city, India, becoming ‘Dada’ (i.e, ‘Local street gang leader’) was my definition of success and respect. As a teenager, I was walking on a thin line between becoming what Indian laws called- ‘Child in conflict with the law’. Today, being a Public Policy scholar at the University of Chicago and living closer to the South Side of Chicago, I am empathetically aware of Chicago’s daily struggle of losing its finest youth to the larger urban crisis of gang violence. Being exposed to the international nature of youth gang violence, my heart raced back to my hometown, Pune city, India.

While looking at the urban phenomenon of rise of the Koyta (Machete) Gangs of Pune city, I try to explore this phenomenon of urban youth violence through the lens of a public policy perspective as well as the empathetic eye of a youth who himself was struggling to find his way out from the unforgiving ‘Urban Jungle’.

History of Caste-based Segregation, Urban Migration, and Ghettoization in Pune City

In the case of Pune city, like any other Indian urban settlement, the socially and economically marginalized Dalit-Bahujan population has been historically segregated based on caste occupational identity and concentrated in the outskirts of the old Pune city. This has been further intensified in the period of British colonial urban planning of Pune city in the form of colonial infrastructural development of Pune Railway station, Military Cantonment, Khadki Ammunition Factory, and Yeravada Central jail. This colonial infrastructure was mostly situated outside of the old Pune city. These colonial institutions became urban focal points around which racially segregated 'servant' colonies of lower caste dalit-bahujan communities got settled organically.

This rural-to-urban migration also intensified in events like the Deccan agrarian distress. After India’s Independence in 1947, many Bahujan families migrated to the urban cities of Maharashtra, like Pune city, in search of livelihood. Anti caste social movements and religious conversion of erstwhile untouchable castes into Buddhism under the leadership of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar also created the wave of rural to urban migration of Dalit communities in Maharashtra in the urban centers such as Pune city. Such rural to urban migration was considered a sign of social and cultural denial of old caste-ridden social, political, and economic exploitation by Dalit-Bahujan communities. Famine-affected decades of the 1960s and 1970s also witnessed the distressed migration of the Dalit Bahujan laborers from the rural parts of the Maharashtra state to the industrial towns in Pune and Pimpri Chinchwad to work in public and private enterprises like Hindustan Antibiotics, TELCO, Bharat Forge, and Khadki Ammunition factory, etc. These patterns of immigration made the urban demography and urban identities of the Pune city residents a spatially and sociologically complex, layered phenomenon.

Emergence of Pune City as the Auto-IT Hub of India

The 1990s were the landmark decade when India took the economic policy decision to embrace Liberalisation, Privatisation, and Globalisation to unleash its economic potential. The urban middle class, mostly comprising the upper caste communities of Indian society, was in an economically and educationally better-off position to reap the benefits of these winds of globalisation in India's urban transition. This era marked the massive waves of the population influx due to Pune city’s new urban transition in the form of the IT (Information Technology), Industrial, and Auto hub. This is the same time period when Pune witnessed the emergence of its own local and immigrant urban middle class. This new urban middle class intensified the aggressive urbanisation of the surrounding agrarian villages of Pune city. This further intensified the process of urban gentrification of Pune city, where an affluent middle and upper middle-class population, mostly comprising of upper castes, started occupying the spaces of Pune city, which were previously inhabited by the local Bahujan communities. This urban gentrification also intensified in its criticality by the new wave of migrant upper caste labor force belonging to the IT and auto manufacturing sector from South and North India. Instead of forming an organic unit within the preexisting social, cultural, and economic milieu of local urban Bahujan communities, this migrant population segregated itself in the residential townships and gated communities in the areas previously inhabited by the Bahujan population. This population migration and its gentrified settlement patterns further isolated and disenfranchised local Bahujan communities, pushing them to face the combined effect of historically colonial, racially segregated, as well as the contemporary caste-segregated urban life of Pune city. these also created dislocation of Bahujan communities at the urban margins of the Pune city due to pressures of caste and class based urban gentrification in the post 1990s Pune city. Nationwide large-scale rural-to-urban migration of young Bahujan demography also further complicated the population migration in Pune city, developing intense pressure on the land, Housing, jobs, health care, and public infrastructure. This also created a skyrocketing of the urban real estate and a pressurising transition of the Agricultural and Forest land surrounding Pune city into Non-Agricultural residential and commercial urban land tracts. This also disenfranchised the local community from their erstwhile settlements and pushed them into economic and social margins in fastly fast-developing Pune urban metropolitan region. These led to distressed rural Bahujan populations ending up in the caste segregated, resource-strained Bahujan urban ghettoes at the outskirts and urban pockets of Pune city for their survival. It made them vulnerable to intense economic inequality, political and social marginalization, and degradation of their human dignity.

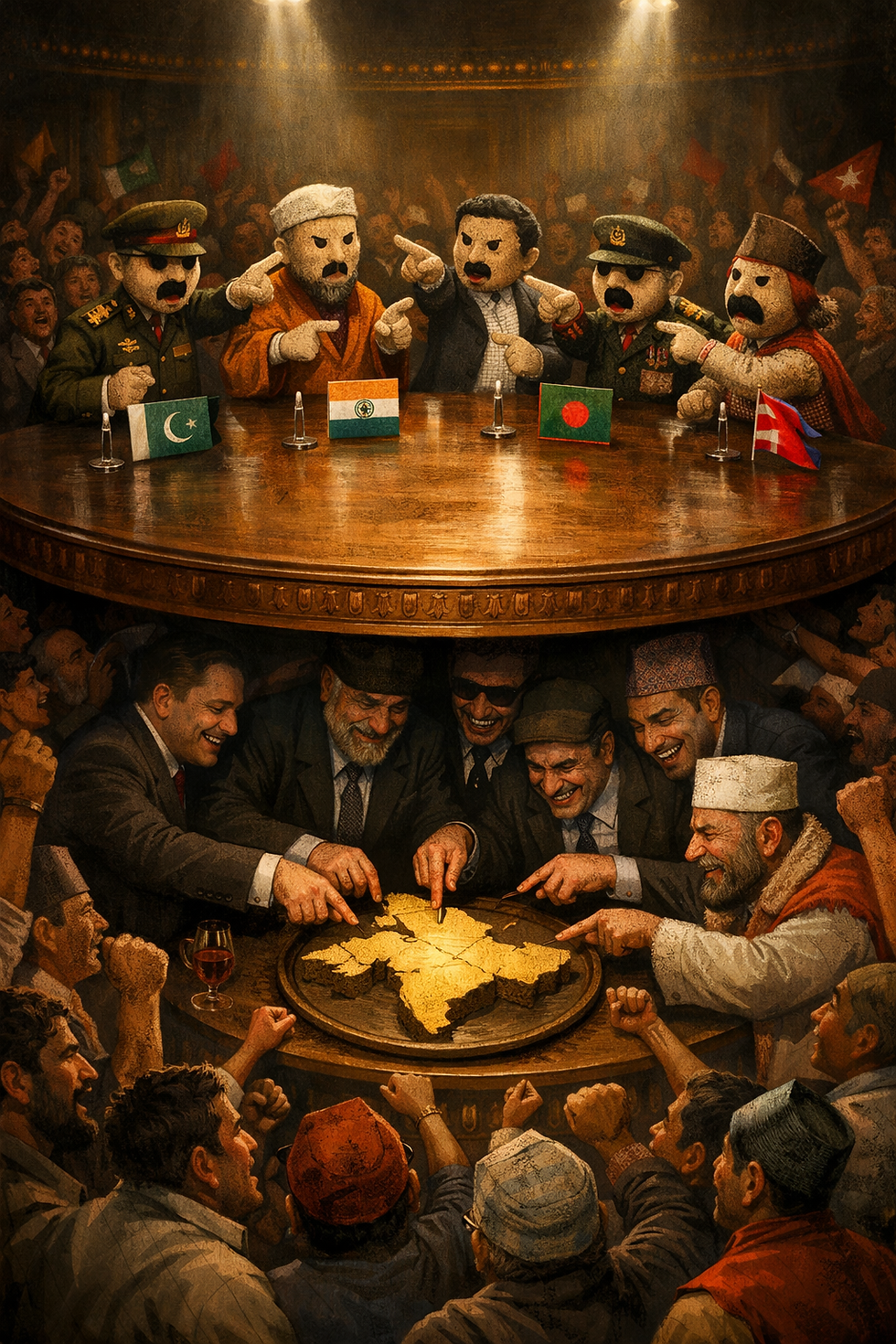

Pune’s Koyta (Machete) gangs: a symptom of the larger urban crisis

Most of the juveniles and youth who engage in koyta gang activities belong to such segregated, distressed urban settlements of Pune city. These urban youth mainly belonged to vulnerable families and community backgrounds. Among these youth, backgrounds of unemployment, dropping out of school, absence of one or both parents, alcohol and substance abuse, food and housing insecurity, domestic and sexual violence, cases of clinical depression, experiences of police brutality, etc., are common recurring experiences. All these themes are not the output of personal experiences but are byproducts of systemic urban social, political, and economic disenfranchisements of a whole section of the urban population. Hence choices these youth make cannot be understood without understanding the systemic disenfranchisement of these youth. The combination of race or caste-based urban ghettoization makes these youth more vulnerable to anti-social activities, crime, and criminality. It makes them more susceptible to seeking their social support systems elsewhere in the form of the underground youth gang culture.

Hidden epidemic of the mental health crisis of at-risk youth at urban margins

Urban youth living at the social, economic margins today face intense pressure in their daily lives to keep up with the rapid changes in their undignified, disenfranchised individual and public lives. They also struggle to define their self-identity. These stress factors, along with material insecurity, vulnerable families and neighborhoods, erosion of the social support system, and inability to fulfil the material expectations of urban life, negatively affect the emotional and psychological vulnerability of these youth. This vulnerability develops a negative sense of personal dignity and structural stigma within these urban youth. These can be reflected in the mental health issues and rising cases of substance abuse, suicides, and self-harm tendencies among youth, especially those living at the social margins of urban life. The structural stigma of living at the margins of society and the apathy of mainstream society to accept these youth as dignified members of urban life further intensifies their exclusion from mainstream urban society. This exclusion develops a combination of rage and a desire for belonging within these youth. These aspects can be seen in their cultural expression in the form of underground gang culture and at-risk behavior, which at times mutate into antisocial behavior, bouts of rage, crime, and criminality.

Social media beef, glamour, and iconography of troubled Anti Hero

Wider exposure to social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Reels allows these urban youth to confidently promote and shape their self-image. Images, story narratives, symbolic language, characterization, and music choices from these social media content reflect their desire to explore meaning and self-dignity in their daily lives of deprivation as well as social and cultural rebellion against the mainstream notions of social and cultural civility.

In the case of Pune-based Koyta gangs, the self-images youth are expressing through their Instagram and other social media handles are mostly the combination of the glamorous, reactionary, violent, enraged, troubled Khalnayak (antihero) who is misunderstood by society but confident in his self-righteous image.

One can also observe another interesting pattern of self-glamorization from these youth and juveniles by taking symbolic references from other young criminals. Recent Instagram and YouTube video trends in India glorify the iconography of Durlabh Kshayap, a slain young gangster from Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, with his signature black shirt, black shoulder cloth, and tilak on the forehead. These youth use such symbols to self-express themselves as follower of the cult of death and destruction, as devotee of the Hindu god Mahakaal (Lord Shiva’s incarnation of death and destruction). Self-expression through social media content of these youth appears to be a hyper-masculine bravado. Acts like machete-toting, threatening rival gang members, and flexing their street credits and criminal reputation can be observed as their attempt to develop their influence by fearmongering and building criminal notoriety as a part of their social and cultural influence-building.

A crucial point one must observe from individuals involved in the Koyta Gangs regarding their social media content is their desire to communicate their unabashed, harsh social and economic realities and their worldview of growing up as a part of disenfranchised urban life.

‘Police Encounters’ and Change in Organized Crime

The presence of local youth street gangs and organized local gangs belonging to disenfranchised immigrant communities had always been part of Pune city. In the case of Pune, the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act (MCOCA) of Maharashtra state created a strong deterrence against organized gangs by arresting their higher gang leadership. The 1990s also saw Maharashtra state police, especially Mumbai police, resorting to a more controversial route of combating organized gangs present in Mumbai city by practicing the controversial practice of ‘police encounters’ in which Mumbai police ended up ‘neutralizing’ hundreds of gangsters from various organized gangs in Mumbai. It did push organized gangs in Mumbai to either leave Mumbai, go underground, or change their old ways of gang operations. Although decreasing visible instances of violent gang wars, knee-jerk police actions against organized gangs by Maharashtra Police in the 1990s could not finish the criminal underworld entirely. Instead, these criminal gangs transformed themselves into new versions of criminal institutional structures that continued operations at the grey margins of law and political economy, engaging in activities like round tripping, Hawala, online gambling, and acting as land mafia. These intense police actions created a spillover effect on the functioning of the local Pune criminal gangs. It altered the functioning of the Pune-based local gangs associated with the bigger Mumbai-based criminal underworld, making their operations more decentralized in nature. Encounters of key gang leaders created a leadership vacuum among criminal gang operations and a loose grip over the lower gang enforcers in Pune city. This vacuum was filled by the emergence of new decentralized street gangs consisting of local young adults and juvenile gang members competing for influence on the local gang territories in Pune city.

Nexus of Organized Criminal Gangs and Koyta Gangs-

Unlike accountability to the centralized gang leadership, Koyta gangs practice a local model of criminal economy by delivering their ‘service’ independently based upon a ‘client needs’. They also demand money by threatening residents, shopkeepers, and industrialists of special industrial zones around Pune city. These Koyta gangs today act as a local enforcer to the bigger organized criminal gangs. This method of functioning distances the central leadership of the bigger organized gangs from law and enforcement investigation. Today, more Koyta gangs are involved in providing their ‘muscle’ to local strongmen to help them forcefully acquire prime real estate properties. Since there are numerous gangs that have emerged in Pune city, they have also started to compete for more gang influence in multiple areas of Pune city. This led to more violent confrontations between the competing gangs. This has also increased the intensity of the fearmongering tactics like public attacks, vandalizing houses, shops, public areas, and vehicles of residents.

Reinforcing Gang Network Through the Correctional System

Considering these aspects, it is important to understand the response of the Indian correctional system. The Indian legal system considers different correctional treatment to juveniles than for adults. According to the Juvenile Justice Act, these juveniles cannot be tried in a court of law designed for adults. These arrested juveniles were shifted to government juvenile reform schools, after which they were rehabilitated back to society. At times, instead of reforming the juveniles, these juvenile reform schools/correctional facilities act as institutional nodal points where juvenile offenders are conditioned into hardened juvenile delinquents. In the case of incarcerated young adult members of gangs, prison becomes a ‘networking ecosystem’ where they connect with incarcerated veteran organized gang leaders, who mentor them into becoming hardened offenders. This institutional system reinforces the tenacity of gang networks, with young gang leaders adopting learned tactics from veteran gangsters to intensify their gang operations.

Conventional State Response to These Urban Gangs

In the case of Pune city, the response of the Maharashtra state government and law enforcement agencies to these urban youth gangs mostly focused on treating these elements as a threat to public safety and a direct challenge to the law and order of the city. Hence government machinery's response against it can be seen by waging war against urban gangs by heavy-handed crackdowns on gang operations and arrests of these youth. Although the dynamics of crime and urban gangs are changing significantly, the response from the political and police leadership seems to be limited to their traditional response in the form of hardline police action against urban gangs. Political leadership in Maharashtra also refuses to understand the deeper systemic issues creating this urban crisis in the first place. This political approach towards the Koyta gangs can be observed in the form of recent responses of key political individuals like Maharashtra state Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and current Deputy Chief Minister of Maharashtra Ajit Pawar advocating the hardline rhetoric against the Pune-based Koyta Gangs. From these responses, we can observe that political and police leadership look at the urban youth gangs as merely a law-and-order issue and not as the totality of a deeper urban social-economic crisis.

Way Forward

The rise of street youth gangs across cities worldwide is not merely a law-and-order issue—it is a mirror reflecting deeper systemic failures of our highly unequal, uprooted, and disenfranchised urban societies. The case of Pune’s Koyta gangs is just the tip of the iceberg, shaped by rapid urbanization, distressed migration, unemployment, aggressive consumerism, and entrenched social inequality. More importantly, it reveals the lived reality of marginalized youth, historically excluded from equal access to education, housing, health, and dignified employment. Their turn towards gangs is not simply criminal behaviour—it is a combination of survival strategy, a coping mechanism, economic aspiration, and at times, an act of resistance against the apathy of mainstream society that refuses to recognize them as equal citizens.

If we continue to see these youth only through the narrow lens of “gang members” or “super predators,” we reduce their humanity and trap ourselves in a cycle of endless conflict between gangs and law and enforcement. Excessive reliance on force alone will not solve this crisis. What we need instead is a bold, inclusive, and forward-looking urban policy framework that addresses the root causes of urban inequality.

This framework must begin by addressing the social and economic deprivation that pushes many young people toward the margins of urban life, through policies that ensure affordable public housing, the creation of education, and sustainable employment opportunities. Equally important is the reimagining of policing: not as a force that instils fear, but as a community-centered institution that builds trust, cooperation, and mutual respect. Alongside this, we must invest in holistic health initiatives that go beyond physical care to include mental health services, domestic violence prevention, and substance rehabilitation programs—acknowledging the interconnected challenges these urban youth face. At the heart of any long-term solution lies the empowerment of youth themselves. Cities must invest in innovative schooling programs, access to sports, platforms for cultural expression, skill development, and entrepreneurship opportunities, thereby offering pathways that nurture both dignity and potential. Finally, the creation of strong social safety networks, public spaces, and the cultivation of an inclusive urban culture are essential, ensuring that no young person feels abandoned or invisible in their own city. By weaving these elements together, we can build cities that do not just control or contain their youth but truly embrace and uplift them as vital stakeholders in shaping the urban future. Equally important, police and city administrations must work hand-in-hand with community leaders, artists, social media influencers, reformed gang members, and families affected by gang violence. These voices can serve as bridges of trust, communication, and transformation. Ultimately, embracing urban youth as our own—not as threats to be neutralized but as future citizens to be empowered—is the only sustainable path forward. Their dignity, safety, and belonging must be seen as inseparable from the well-being of our cities.

As the African proverb wisely reminds us: “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” If our cities fail to embrace their most vulnerable, the fires of their alienation will consume us all. But if we invest in their humanity, we create not just safer streets but stronger, more compassionate, and truly inclusive cities.

Comments