Problems of being 'Desi'-The Untold Truth of Desi community

- anand kshirsagar

- Nov 15, 2025

- 6 min read

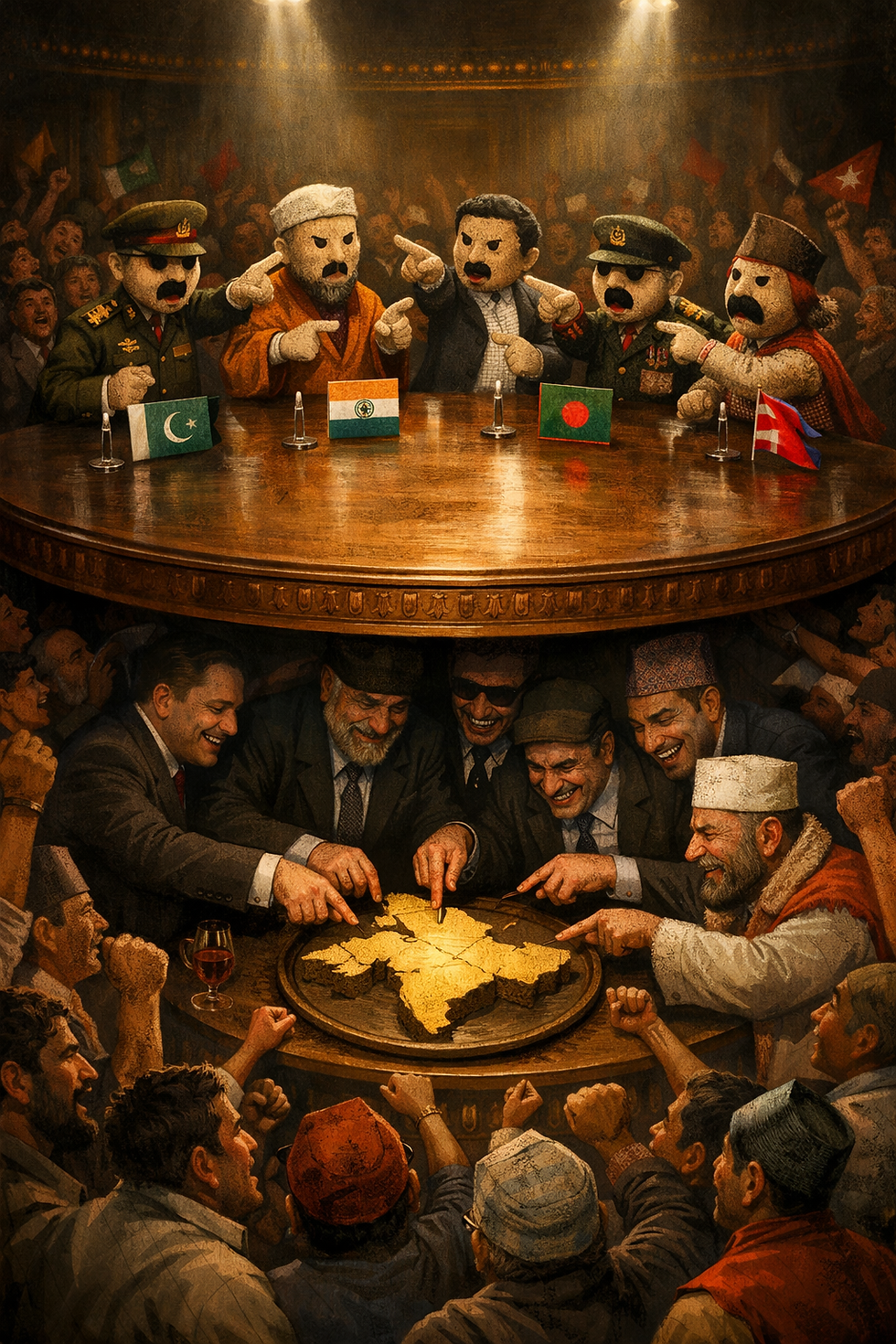

Across the world today, millions of South Asian immigrants from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka proudly describe themselves as “Desis.” The term is invoked as a unifying label for people who share a South Asian cultural and social background. Although South Asians have been migrating for more than a century—through waves that preceded both World Wars—the contemporary meaning of “Desi” has undergone significant transformations. Being “Desi” today has become a point of pride, self-confidence, and dignity for the South Asian community. Yet beneath the colorful festivals, delicious food, Bollywood films and music, strong community bonds, and cultural nostalgia lies a deeper social pathology embedded within the Desi identity of the South Asian diaspora.

Who Constitutes the Desi Community?

In its modern form, Desi identity is largely shaped by South Asians who migrated to North America, Europe, Australia, and West Asia after the Second World War. From the 1950s to the early 2000s, liberal immigration periods in US, Canada, Europe, and Australia facilitated the entry of highly educated South Asian professionals—engineers, doctors, academics, and later IT workers. Alongside them exists a parallel labour migration stream of semi-skilled and unskilled workers, especially in the Gulf nations, where millions of South Asians work in hospitality, construction, agriculture, transport, and domestic labor, often under precarious or exploitative conditions.

Despite dramatic class and caste differences between these groups, the term “Desi” collapses all distinctions into a single, simplistic identity. Although the social, economic, and educational profiles of the South Asian diaspora are diverse, it is the upper-caste, urban, English-speaking, and highly educated sections that have been most visible and most empowered to define the social and cultural narrative of Desi identity.

Cultural Life and Community Organization of the Desi Community

Desi communities abroad maintain vibrant social networks anchored in festivals such as Holi, Diwali, Eid, Ganesh Chaturthi, Navratri, Vaisakhi, and Christmas. Many South Asian student associations organize cultural programs built around a mainstream understanding of Desi identity. These events serve as public expressions of belonging, shaped by shared religious rituals, food, clothing, and Bollywood-driven popular culture.

Yet this celebratory landscape masks a homogenized cultural template—dominated by North Indian, Hindi-Punjabi-Urdu-Gujarati sensibilities—that overshadows South Asia’s rich linguistic, ethnic, and regional diversity. This “mainstream Desi culture” becomes a symbolic hegemony that erases marginalized identities and flattens the complexity of South Asian life. It functions as a tool for reproducing and consolidating cultural power among South Asian immigrants, reflecting a common cultural sensitivity that is predominantly Brahmanical, upper-caste Jaat Sikh, or upper-caste Ashraf muslim in nature.

The Social Pathology of Desi Identity

As carriers of “Desi culture,” many South Asian immigrants reproduce not only its celebratory elements but also its regressive social structures. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar warned that although caste originated in South Asia, it could become a global instrument of social and economical inequality, because South Asian migrants carry caste consciousness with them. In diaspora settings, Desi identity often becomes a mechanism to maintain caste privilege, patriarchal norms, and communal stereotypes while rejecting genuine social dialogue about the reproduction of caste-based power disguised as Desi collective life.

Many Desis exhibit a paradoxical worldview: glorifying ancient South Asian traditions while simultaneously craving validation from white-majority Western societies. Cultural pride becomes entangled with colonial trauma, aspirational whiteness, racist attitudes toward non-white communities, and a deep reluctance to confront the social evils embedded in South Asian societies.

Bollywood and the Caste-Sanitized Representation of the Desi Diaspora

Bollywood—both as an industry and as a cultural system—has significantly shaped global understandings of what it means to be “Desi.” Since the 1990s, globalization has intensified diaspora-centric storytelling in Hindi cinema. Films like Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, Pardes, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna, and My Name Is Khan portray the immigrant experience through an upper-caste lens that celebrates the self-made, law-abiding, family-oriented “model minority.”

These narratives erase caste, labor exploitation, intercaste tensions, and everyday gender violence that shape South Asian lives at home and abroad. Bollywood’s upper-caste gaze constructs a glossy, caste-neutral fantasy of the “ideal Desi diaspora community,” marginalizing Dalit-Bahujan, women, and minority experiences. As a result, Desi identity becomes reduced to performances of festivals, food, music, and clothing, while cinema fails as a tool to critically understand South Asian lived realities.

Fractures Within the Desi Community

Although Desi identity claims to be unified, it is deeply fragmented along regional, caste, communal, and linguistic lines. Organizations such as Maharashtra Mandal, Federation of Gujarati Associations of USA (FOGAUSA), Telugu Association of North America (TANA), Federation of Tamil Sangam of North America (FeTNA), and Punjabi-American Cultural Association (PACA) are largely dominated by the upper-caste communities of their respective linguistic and regional groups. Dalit-Bahujan immigrants—including Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, and Christian groups—frequently experience exclusion from these spaces.

In response, they build separate Ambedkarite associations that celebrate the legacies of B.R. Ambedkar, Sant Ravidas, Savitribai Phule, Sant Kabir, Periyar, and Mahatma Phule—figures largely ignored by upper caste Desi organizations. These alternative spaces of Bahujan desi diaspora cultivate egalitarian values, community mentoring, and mutual care, offering a vision of Desi identity grounded in dignity and social justice rather than upper caste social , cultural dominance.

Gender, Patriarchy, and the Burden of Being ‘Desi Women’

The responsibility of preserving “authentic Desi identity” disproportionately falls on South Asian women. Their dress, sexual autonomy, dietary choices, marriage decisions, and mobility are closely monitored within families and community networks. With caste purity as a core anxiety, patriarchal control persists even after migration abroad. Women who challenge these norms often face honor killings, domestic violence, dowry-related harassment, cyberbullying, emotional abuse, and caste-based discrimination—frequently hidden beneath the sanitized image of the model minority household.

In stark contrast, the identity of the “Desi Boy/Desi Munda” celebrates patriarchal, hypermasculine traits, as ‘Desi Boyish Charm’ or ‘Desi Manly Rusticenes’ treating women as secondary members of the community and ‘objects of consumption’. This gendered imbalance forms a central pathology of the Desi gendered social structure.

Hindutva Desi Chest Thumping and the White Nationalist Response

The rise of Hindu nationalism and the consolidation of a Hindu majoritarian identity within India has reshaped Desi behavior abroad. A growing section of the Indian diaspora now identifies not as “Indian American” or “British Indian” but as “Hindu American” or “British Hindu,” placing religious identity above civic belonging. This diaspora Hindutva nationalism produces a rhetoric of cultural arrival—an assertive “Sanatani Hindutva” ego that often manifests as civic indiscipline, disregard for local norms, and ethnic chauvinism.

In an era of social media, such behaviors are easily weaponized by populist white Christian nationalist movements in the West, fueling anti-immigrant sentiment and racist narratives targeting South Asians.

The ‘Model Minority Myth’ of Desi Communities

The Model Minority Myth exposes the contradictions within Desi communities. While many Desis project themselves as self-made, disciplined, and successful, this narrative hides structural advantages these upper communities received from the South Asian society. Upper-caste, urban, English-speaking South Asian immigrants are often beneficiaries of the intergenerational caste-based cultural, economic, educational capital as well strategic formal and informal social networks of opportunities. Many members of upper caste desi immigrants and diaspora deny this fact simply because it goes against their made-up public image of the self-made ‘success story’.

The polished model minority image also conceals persistent social evils such as domestic abuse, caste discrimination, dowry violence, labor exploitation, and even human trafficking—as seen in case like Lakireddy Bali Reddy. Although Desis live within egalitarian Western legal structures, their daily lives often remain governed by South Asian socio-cultural norms. Racist attitudes toward Black, Indigenous, and marginalized communities further complicate their claims to moral victimhood.

Caste-based social boycott remains a powerful deterrent for South Asians abroad, as potent as in South Asia itself. Desi identity thus becomes a functional duality—drawing economic mobility from the West while reproducing caste, gender, and communal hierarchies within insular community life.

What To Do With Desi Identity?

Desi identity, in its current form, is neither transformative nor egalitarian. It offers a false sense of comfortable familiarity to South Asian community, but beneath that familiarity lies a structure of social, political, and cultural power that sustains caste privilege, patriarchal norms, ethnic nationalism, and cultural conservatism. In an era of rising white Christian nationalism, authoritarianism, and global anti-immigrant sentiment, Desi communities must engage in deep introspection rather than relying on the convenient narrative of being a 'model minority'.

Without embracing intercaste Bahujan solidarity and bold socio-cultural reform, Desi identity will remain trapped in the scissors’ effect of simultaneously being victims of racism and perpetrators of oppression against Dalit-Bahujan, Adivasi, minority, and women members of their own community. This hypocrisy has significantly eroded the moral currency of South Asian immigrants and diaspora in their immigrated nations. If unaddressed, it may degrade their social and political legitimacy within Western societies facing the holistic disenfranchisement from the resurgent populist and racist nationalism.

A truly emancipatory South Asian identity can emerge only if the diaspora embraces Anti caste and global social justice traditions—shedding the burdens of caste, patriarchy, communalism, and nationalist chauvinism. The first step is to question the comforting myth that Desis form “one big cultural family.” Every Desi knows, deep down, that such unity is far from reality.

Honest conversations about uniquely Desi social evils—and welcoming anti-caste Bahujan perspectives into spaces such as social media, classrooms, weddings, religious gatherings, family dinner tables, and corporate offices—are essential. Desi identity should not be an excuse for defending South Asian social evils. Instead, it should become a point of honest dialogue through which the South Asian diaspora can reimagine its rightful place in a complex, rapidly changing world, while genuinely sharing and celebrating its cultural beauty with others.

Comments