Bringing ‘Philosophy’ Back to the ‘PhD’: Why 'Doctor of Philosophy’ Needs a Fundamental Reset

- anand kshirsagar

- Dec 11, 2025

- 7 min read

“You so-called experts with your fancy PhD degrees from the posh universities are part of the problem! I see many of you who visit my village every now and then for your 15-day ‘study tours’. But let me tell you one thing... while sitting behind your laptop screen, if you think you can understand my daily problems, then you are cheating yourself and also wasting my time. You can’t even differentiate between a rooster and a hen.”

When 68-year-old Gundappa Kadagi, a rustic farmer from Pandharpur taluka in Maharashtra, said these words to me, his sarcasm struck like a slap of truth. His frustration captured the widening disconnect between the so-called PhD research experts and the lived realities of everyday people. His critique reflects something much deeper than a complaint about visiting researchers—it exposes a fracture in the very foundations of academic knowledge production. What he articulated is a crisis not only within the institution of the PhD program but within the intellectual culture that surrounds it.

Across universities worldwide, the modern PhD has drifted far from its original intellectual vision. Although the degree still carries the title “Doctor of Philosophy,” philosophical inquiry, critical reflection, and the pursuit of fundamental questions have all but vanished from doctoral training. Instead, the typical PhD scholar is shaped into a ‘research bureaucrat’—moulded by a technocratic pipeline that rewards methodological precision, moral flatness, political neutrality, careerist ambition, and the clinical pursuit of publishable outputs. Intellectual depth is no longer the driving force behind doctoral work; publication metrics are.

As quantitative tools, computational techniques, mathematical modelling, and instrument-heavy methods dominate research training, the central skills of deep thinking—critical analysis, conceptual clarity, ethical reflection—have become secondary. The consequences of this shift extend far beyond academia: they shape public culture, contribute to mistrust of experts, widen the gap between the intellectual class and everyday people, and indirectly fuel cynicism toward democratic institutions. Ironically, the academic pipeline of the PhD itself bears a significant part of the blame.

The Rise of the PhD as the Technocratic Scholar

Today’s doctoral candidate moves through a predictable assembly line: master the techniques, run the statistical models, acquire software expertise, publish papers, and ultimately chase a tenured academic job. This structure is heavily influenced by the belief that doctoral research must contribute directly to industry and economic productivity. The PhD is imagined as a research pipeline that produces “applied experts” who can serve the technical needs of institutions, industries, and governments.

But this approach is fundamentally limited—it rarely questions the broader ecosystem in which these institutions operate. Knowledge creation becomes evaluated through a cost-benefit lens, measured in terms of return on investment: How many years were spent? How many papers were produced? How many grants were secured? What salary awaits after completion?

This mentality produces scholars who are technicians of data-rich information rather than creators of fundamental knowledge. They conform to the expectations of their discipline rather than challenging them. Their intellectual imagination becomes restricted by established methodological dogmas. The result is an academy that churns out “batch-processed” PhD graduates—smart, efficient, and technically competent, yet philosophically hollow. Many remain confined within their disciplinary silos, comfortably insulated in intellectual echo chambers.

Philosophy as the Foundation of Intellectual Inquiry

Philosophy is not merely one discipline among many; it is the foundational ground from which all knowledge systems emerge. It cultivates conceptual clarity, intellectual courage, and the capacity to ask deeper questions—even those that disrupt the assumptions of one’s own field.

A truly philosophical PhD program does not rely solely on technical mastery of research tools. Rather, it encourages scholars to identify gaps in existing knowledge, question the question itself, explore the meaning behind their research, and recognise the interconnectedness of diverse domains. Philosophy pushes the researcher beyond mechanical method application toward an engaged, thoughtful relationship with ideas, people, and the phenomena they study.

Fundamentally, philosophical inquiry reveals that every research project is also a form of self-inquiry. The ancient philosophical command—“Know Thyself”—remains the fountainhead of all meaningful research. Without such grounding, inquiry becomes sterile, detached, and directionless.

Escaping the Limits of Technical Line-Staff Thinking

In many ways, PhD students today reduced to the position of the technical line-staff within the global political economy of research—skilled workers who keep the machinery running but are rarely asked to reimagine the machinery itself. This is a dangerous limitation, especially when the world faces crises that demand expansive, interdisciplinary thinking: climate change, racial, caste, and gender violence, technological disruption, widening economic inequality, pandemics, and threats to democratic institutions.

These problems cannot be solved through technical data proficiency alone. They require intellectual flexibility, philosophical depth, and the willingness to think beyond the constraints of existing frameworks. Philosophy broadens the scope of inquiry by encouraging scholars to engage with abstract, complex questions that defy reduction into neat datasets or quantitative models. It helps researchers recognise underlying assumptions, question dominant paradigms, and conceptualise new ways of seeing the world.

Without this grounding, scholars become trapped within narrow research questions defined by available tools instead of expanding the horizons of intellectual creativity. The absence of philosophical training ultimately impoverishes the capacity of research to imagine new possibilities.

Rebuilding the Public Intellectual Tradition

The purpose of a PhD should not be the production of narrowly focused specialists who care only about their publication metrics and tenure-track viability. A philosophically grounded PhD produces public intellectuals—thinkers who engage with society, articulate ideas clearly, confront uncomfortable problems, and contribute to public thought. Technocratic training, by contrast, produces scholars who remain trapped in ‘intellectual echo chambers’, technically proficient but intellectually timid. Reviving philosophical education is essential to restoring an academic tradition that values independent thought, public engagement, and moral responsibility.

Recognizing the Political Nature of Knowledge Creation

Knowledge is never neutral. Every aspect of research—from the choice of topic and definition of data to methodological selection and interpretation—is shaped by political, social, and cultural values.History provides painful lessons: the Tuskegee Syphilis experiments, the exploitation of enslaved Black women in gynaecological medical experimentation in US, and numerous studies conducted without consent or ethical concern. Even today, many Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) run by institutions of the Global North rely heavily on populations in the Global South, raising philosophical questions about power, exploitation, and the politics of data. It raises the questions like- Who becomes the object of study? Whose gaze shapes the research? Whose bodies are scrutinized? Which societies become the world’s “human data laboratories”?

Without philosophical grounding, many PhD scholars cling to the illusion of methodological neutrality, hiding behind the façade of objectivity. Philosopher-trained scholars are forced to confront their positionality—and in doing so, acknowledge that research is inherently political.

The Illusion of 'Non-Political Objectivity' in the PhD Research Culture

The claim that PhD research is ‘objective and apolitical’ is itself a political act. The politics of specialists lies in the projection of neutrality—experts who claim scientific detachment often mask the power they wield in shaping public opinion, policy, and discourse. This assertion of perceived research neutrality produces intellectual arrogance and shields researchers from public scrutiny.

The insistence on objectivity ignores the simple truth that no researcher is free from political influence or human experience. It transforms their positionality into a forbidden topic, fostering a culture that equates methodological precision with moral superiority. Such detachment fuels a bureaucratic form of knowledge creation that is politically consequential yet refuses to acknowledge its consequences.

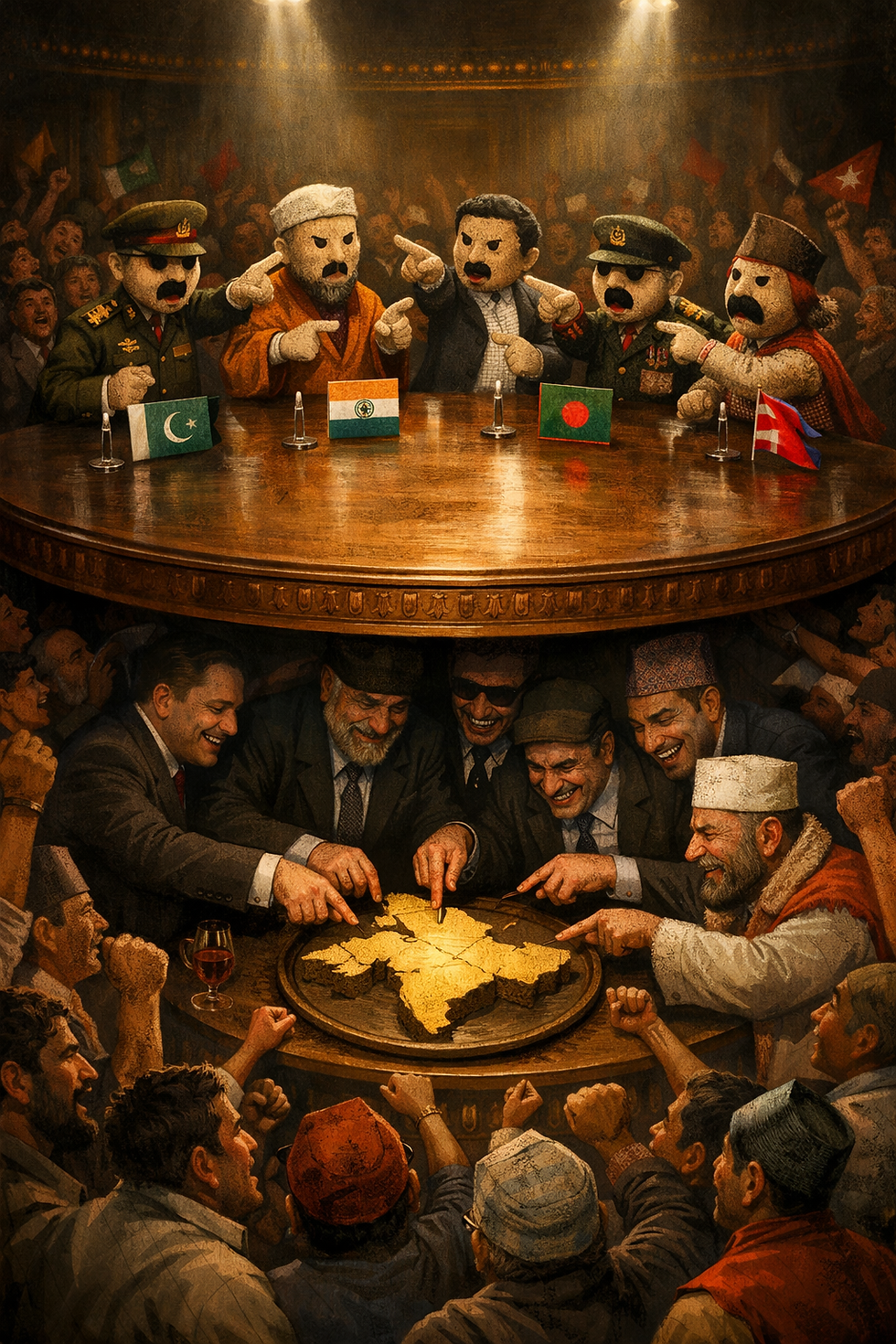

Elite Technocrats and the Rise of Anti-Intellectual Populism

This cultivated detachment between expert and public disrupts the natural social and cultural contract that once enabled knowledge to circulate democratically between intellectuals and the masses. When people feel excluded, talked down to, or rendered irrelevant by ‘hegemony of the intellectual class’, they seek ‘alternative sources of knowledge’—often pseudo-scientific, conspiratorial, or politically manipulated.

This contributes directly to the rise of anti-intellectual political populism. Across the world, trust in experts is eroding. It is observed that survey response rates of respondents have been dropping significantly. Communities historically marginalized or misrepresented view experts with suspicion, perceiving them as parachuting elites who study them from a distance without genuine human connection.

When philosophy disappears from doctoral education, researchers lose the ability to relate, empathize, or engage meaningfully with people. What collapses is not merely public trust in experts—but the very foundations of democratic culture.

The Researcher–Teacher Divide: A Crisis in Academic Purpose

Today’s PhD holders are expected to be both researchers and teachers, but the academy rarely acknowledges that technical expertise does not automatically translate into teaching ability. The university system incentivizes research productivity, grant acquisition, and citation counts—not teaching excellence.

As a result, many professors become brilliant researchers but ineffective educators. They can perform sophisticated statistical analyses yet struggle to explain concepts to students or connect knowledge to human experience. When teaching becomes secondary, universities lose their democratic purpose as spaces for shared intellectual growth. This identity divide between research expertise and educational responsibility is not just pedagogical—it is philosophical. It reflects the broader failure of the PhD to cultivate reflective, empathetic scholars grounded in humanistic inquiry.

The Limits of Objective Data-Driven PhD Research: A Feminist Critique

Feminist scholarship has long pointed out that the dominance of quantitative, econometric, and mathematically driven methods is not gender neutral. These methods are framed as rigorous, objective, rational, robust, scientific, and hence masculine in its research understanding, while qualitative approaches are dismissed as subjective, supplementary, less scientific, impure and hence more feminine. This reproduces epistemological hierarchies resembling caste systems—purity versus pollution, objective versus subjective, mathematical versus experiential. Such binaries obscure the nuance, humanity, and unpredictability captured by qualitative research. Philosophy provides the tools to interrogate these hierarchies, challenge methodological dogmas, and build more inclusive models of knowledge creation.

Why Philosophy Must Return to the Centre of the ‘Doctor of Philosophy’

Reintegrating philosophy into PhD training is not a nostalgic project—it is a necessity. Philosophy equips scholars to recognise their own limitations, combat intellectual arrogance, and interrogate the assumptions underlying their methods. It nurtures scholars who are imaginative, critical, ethically grounded, and socially engaged.

A philosophically enriched PhD restores the original purpose of the degree: to produce thinkers, not technicians. Meaning-making lies at the heart of all research, and philosophy is the lens through which meaning emerges. Bringing philosophy back into doctoral training is essential for academic integrity, intellectual courage, and democratic survival.

PhD scholars are not merely knowledge producers; they are potential intellectual leaders. Democracies thrive only when their intellectual class is reflective, empathetic, and grounded in human experience. As the challenges before us deepen, we need scholars capable of combining technical expertise with philosophical depth, ethical reflection, and interdisciplinary thinking.

Without philosophy, the PhD becomes a sterile technical credential.With philosophy, it becomes a transformative journey toward truth, wisdom, and responsibility.

And perhaps, with more philosophy in the Doctor of Philosophy, the next time a researcher visits Pandharpur, Gundappa Kadagi might take them seriously knowing they can finally tell the difference between ‘rooster and a hen’.

Comments