Counting Castes, Building Democracy : Why India Needs a Caste Census Now

- anand kshirsagar

- Aug 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

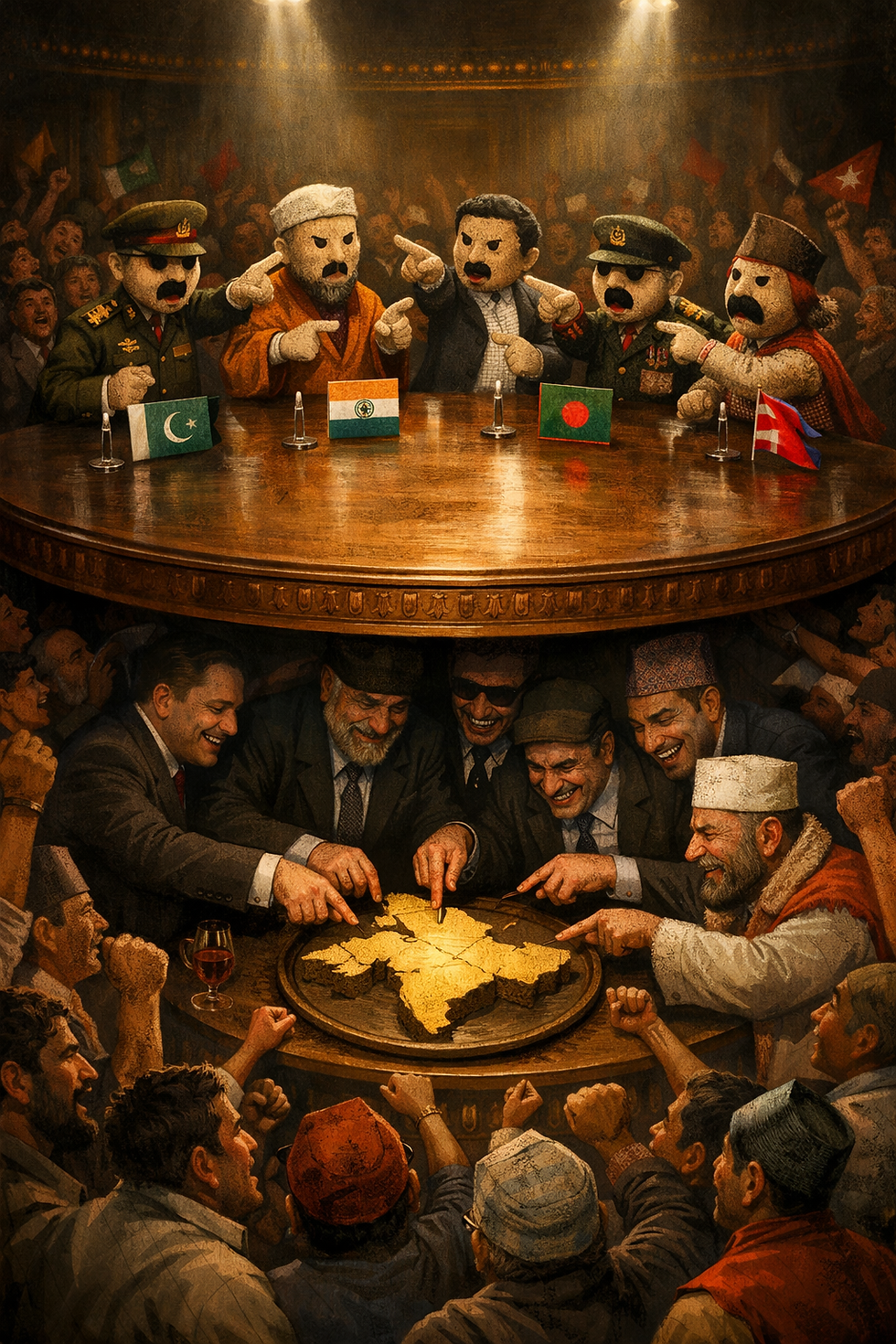

India stands at a critical juncture in its democratic journey. As the world’s largest democracy prepares to undertake what could be the largest data collection exercise in human history—a caste census—the stakes are not merely statistical. They are moral, political, and deeply social. A caste census is not simply about collecting numbers; it is about ensuring justice, representation, and the possibility of a more equal society.

Why a Caste Census Matters

Caste has been, and continues to be, one of the most defining features of Indian society. It shapes people’s life chances in areas as diverse as education, employment, health, and ownership of resources. Yet, despite the profound role caste plays in structuring opportunity, the Indian state does not possess comprehensive, up-to-date data on caste groups outside of the Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) categories recorded in the decennial Census. The last time caste data was collected comprehensively was in 1931caste census—nearly a century ago.

Since then, India has transformed into an independent democracy, an economic powerhouse, and a society in flux. But without reliable caste data, policy-making remains hampered by guesswork and outdated assumptions. A caste census would fill this vacuum.

Informing Public Policy

Public policy cannot be built on partial or outdated information. In the field of health, caste often determines access to healthcare and nutrition, with marginalized groups experiencing higher rates of maternal mortality, child malnutrition, and chronic illnesses. Without caste-disaggregated health data, it becomes impossible to design interventions that can effectively address these inequities. Similarly, in agriculture and the rural economy, land ownership continues to be heavily skewed along caste lines. A caste census would help reveal who owns resources, who works as landless labor, and how agricultural policies are impacting different communities, insights that are crucial for rural development and poverty alleviation. The same is true in education and employment, where reservation policies form the backbone of India’s social justice framework. Yet without updated caste data, we cannot know whether these policies are reaching the intended beneficiaries, whether some groups remain underrepresented, or whether new inequalities have emerged. Even when it comes to economic mobility, comprehensive data on income, occupation, and upward movement across caste groups would allow policymakers to track whether historically marginalized communities are managing to break free from cycles of poverty or whether they continue to be trapped by systemic barriers. In short, a caste census would lay the foundation for evidence-based policymaking across sectors, shifting debates from anecdotal claims to empirical evidence and enabling governments to allocate resources more fairly and effectively.

Beyond Data: A Question of Justice

But the importance of a caste census extends far beyond technocratic policy design. It is, fundamentally, about social justice.

Democracy thrives when all voices are heard and represented. If caste shapes access to power and resources, then ignoring caste data is akin to silencing large sections of society. A caste census would recognize the lived realities of marginalized groups and affirm their place in the national narrative.

Critics of caste census sometimes argue that a caste census will “divide society.” This argument, however, misunderstands the role of data. Caste divisions already exist; pretending they do not only entrenches inequality further. Collecting accurate data does not create inequality—it reveals it, making it possible to address. Silence does not heal social wounds; recognition and redressal do.

Democratic Participation and Accountability

The call for a caste census is also a call for greater democratic accountability. India’s democracy is vibrant but unequal. Representation of marginalised section of Indian soceity in legislatures, bureaucracy, academia, and the private sector remains skewed. By making visible the actual distribution of caste groups across professions and regions, a caste census would force institutions to confront their biases and shortcomings.

Moreover, the exercise itself—mobilizing millions of enumerators to document the realities of every household—would be a profound act of democratic participation. It would send a clear message that every community counts, and that the state recognizes their struggles and aspirations.

The World’s Largest Data Collection Exercise

Undertaking a caste census would not only be unprecedented in scale, it would also be historic in scope. It would be the largest data collection exercise ever attempted anywhere in the world, covering over 1.4 billion people across thousands of castes, sub-castes, and communities.

Handled carefully, with robust technology and data safeguards, this exercise could set a global standard in inclusive governance. Nations across the Global South, struggling with their own legacies of inequality, would watch closely as India demonstrates how data can be harnessed for justice in a democracy of continental proportions.

Conclusion: From Numbers to Justice

A caste census is not simply about counting people. It is about acknowledging histories of exclusion, measuring present inequalities, and laying the groundwork for a more just future. It is about moving from invisibility to recognition, from assumptions to evidence, from tokenism to true equality.

In the world’s largest democracy, the demand for a caste census is a demand for deeper democracy itself. To refuse it is to accept ignorance and injustice as the status quo. To embrace it is to affirm that every citizen matters, and that data can be the first step toward dignity, equality, and justice for all.

Comments