Decoding Peter Navarro’s ‘Brahmin’ Remark

- anand kshirsagar

- Sep 8, 2025

- 6 min read

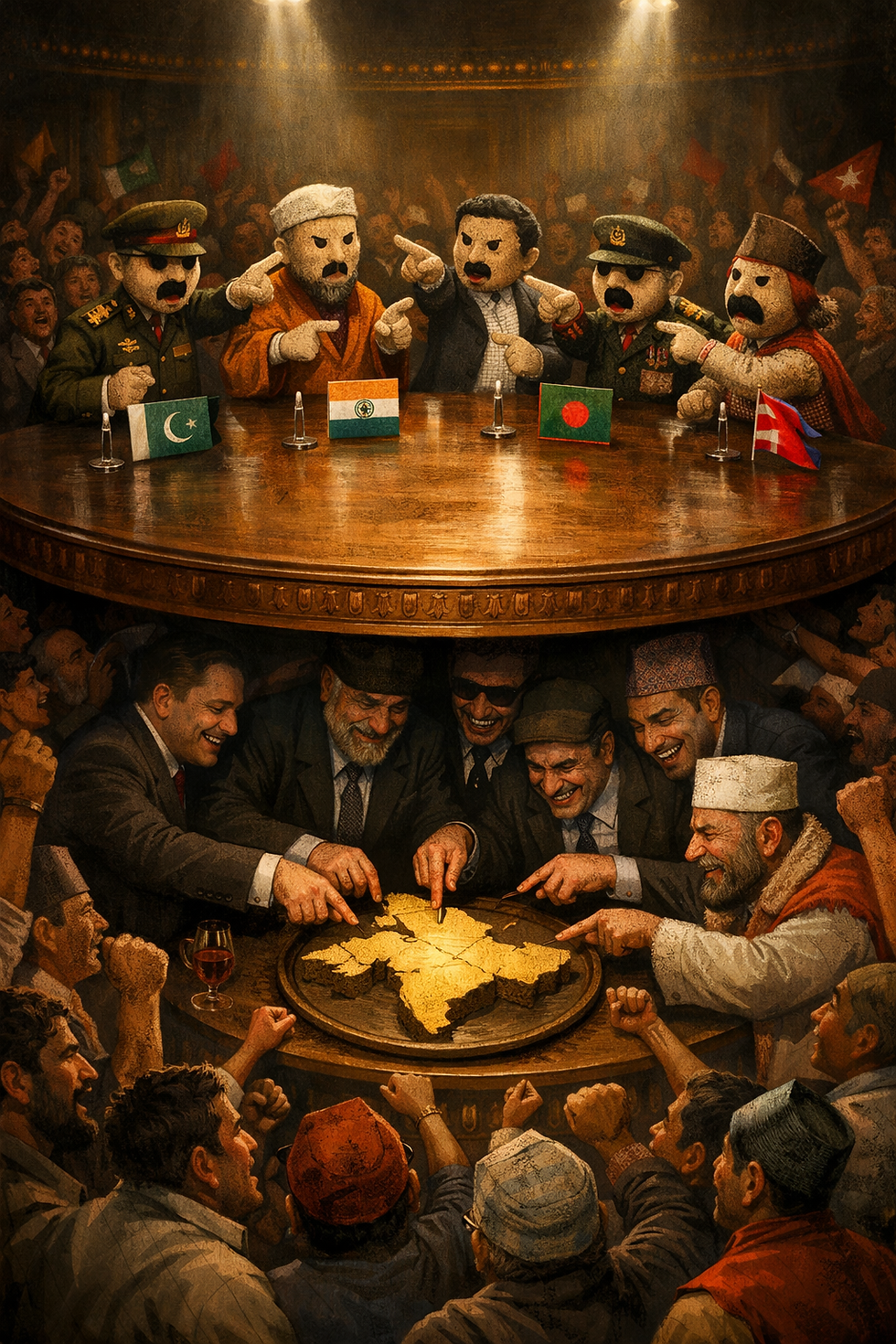

Recently, Peter Navarro—former Trump administration trade adviser—sparked controversy with his statement on India’s oil trade with Russia and its growing role in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). What caught attention was not simply his critique of India’s balancing act between the Russia and China, but his pointed jibe: that “In international oil trade between Russia and India, Brahmins benefit at the expense of ordinary Indians.”

The remark has been met with confusion, outrage, and dismissal in India. Yet rather than brushing it off, it is worth unpacking what Navarro may have intended, what he misunderstood, and why such language—invoking caste categories in discussions of global geopolitics—reveals the deeper political complexities in Indo-US relations today.

Navarro’s Intention: Pressurising Indian Leadership

Indian media and politicians dismissed Peter Navarro’s remark as ignorant, anti-India rhetoric, with some linking it to the term ‘Boston Brahmin.’ While such criticism is understandable given Navarro’s rhetorical track record, his comment raises an overlooked question: the caste-based nature of India’s capitalist elite, both at home and within the diaspora—a point largely ignored by the upper-caste dominated Indian media and political class. At first glance, Navarro’s comment appears to be a clumsy attempt to critique India’s political and economic elites. In his framing, oil trade deals with Russia and India enrich a small section of Indian elites, while the “common Indian” sees little benefit. This rhetorical strategy of economic antagonism—pitting the nations against nations and elites among the nation against its own common people—is a classic populist move, and Navarro has long employed such language in his critiques of global trade.

Who are ‘Boston Brahmins’?

The term ‘Boston Brahmin,’ coined by Oliver Wendell Holmes, described Boston’s elite Protestant families—early settlers who held enduring social, cultural, economic, and political power. In India, a parallel exists in the upper-caste elites—primarily Brahman, Baniya, and Kshatriya (warrior caste) families—who have long wielded similar inherited privilege and influence across Indian politics, business, economics and culture. In the case of Navarro, the choice to use the word “Brahmins,” however, is striking. Was Navarro really engaging with India’s caste system? Unlikely. More plausibly, he deployed “Brahmin” in the American sense, akin to the “Boston Brahmins”—a term historically used to describe a wealthy, insular American elite of the East Coast, New England. In that sense, Navarro was simply signalling that India’s international trade manoeuvres serve its upper-class elites, not its working-class Indian citizens.

Yet the invocation of “Brahmins” is not entirely misplaced. In India, caste does shape who dominates economic, social, business and political networks. To ignore that reality would be to miss the structural roots of elite institutional capture in India.

What Navarro Gets Wrong—and What He Gets Right

There are several reasons to be sceptical of Navarro’s newfound “concern” about caste inequality. He shows little indication of being genuinely interested in the complexity of caste driven political economy in India or among the US-based Indian diaspora. His remark was less a studied sociological observation than a rhetorical weapon in the service of U.S. foreign policy debates.

But there is also a kernel of truth in his statement. India’s caste system has long determined the monopoly over land, capital, education, networks of cultural, social capital and political power. In both India and its diaspora, upper-caste communities have disproportionately dominated business ownership, corporate leadership, and political influence.

In the U.S. today, foreign policy toward India is often filtered through engagement with an elite upper caste diaspora stratum that does not represent India’s vast social diversity. Indian American lobbying groups, business associations, and non-profits—many of them upper-caste dominated Hindus—play an outsized role in shaping Washington’s perception of India. They also constitute one of the most important overseas funding and ideological bases for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The recent demonstration of a massive public event like Howdy Modi in the US reflects this complex caste driven political and financial nexus in Indo-US relations.

Thus, while Navarro’s motives may be opportunistic, his reference to caste privilege inadvertently touches on a larger, underexplored truth: the nature of Indo-US relations today is increasingly mediated through the prism of caste-driven elite networks.

Role of Indian Elite Business Tycoons and Indo-Russian Oil Business

Since the war in Ukraine, Russian oil has been experiencing a price cap of 60dollars per barrel. This has been done to limit the war economy of Russia. From the Russian oil sanctions, Reliance Industries (RIL), led by Mukesh Ambani, emerged as one of India’s largest importers of Russian seaborne oil. Once just 3% of RIL’s Jamnagar refinery’s imports in 2021, Russian crude now accounts for around 50% in 2025. To access price-sanctioned Russian crude oil, the ‘shadow vessels’ are used to bypass G7 vessels, which can be tracked. As of January, 83% Russian crude oil has been transported by these shadow vessels, much of this oil is refined at Reliance’s Vadinar and Jamnagar refineries and re-exported to the EU and US—generating massive profits retained by Reliance Industries Limited.

The Caste Capitalism of Indian Elites and Its Diaspora

To understand why Navarro’s comment resonates, we must situate it within what can be described as India’s “caste capitalism.” Unlike in many other societies, where class mobility is often imagined as more fluid, India’s economic elites overwhelmingly emerge from a narrow band of upper-caste communities—Brahmins, Banias, and other dominant caste groups.

This monopoly is visible in India’s domestic economy, where upper-caste elites dominate finance, industry, media, and academia. It extends into the global economy through Indian American professionals in Silicon Valley, C-suite leadership in multinational corporations, and venture capital networks. The so-called “model minority” myth of Indian Americans obscures this fact: the diaspora’s extraordinary success in the U.S. has been largely an upper-caste phenomenon.

These elites today form the figurative “Brahmins” of contemporary Indo-US relations. They are the cultural brokers, the business partners, and the political donors who proactively contribute to how New Delhi is represented in Washington as well as how Washington should engage with New Delhi. But they also remain socially insulated, their successes detached from the everyday struggles of India’s working poor and marginalized caste communities. It reveals how questions of inequality and exclusion within India reverberate internationally. Just as debates about race and inequality shape U.S. domestic and foreign policy, caste—though less visible to American observers—shapes India’s internal order and its global engagements. Ignoring caste is not a neutral act; it is a choice that privileges the voices of those already at the caste pyramid.

Why Navarro’s Remark Matters

Critics might argue that Navarro was not making a serious sociological claim about caste, and therefore, his comment is not worth overanalyzing. But this misses the point. Language matters. The fact that an American policy figure invoked “Brahmins” in critiquing India’s geopolitical posture indicates a shifting awareness: the old narrative of India as a unified, upwardly mobile democracy is giving way to a recognition of its internal fractures.

It also opens space for a much-needed conversation. If Indo-US relations are to deepen, they must grapple with the reality that India’s elite-driven model does not reflect its broader citizenry. The benefits of trade deals, technology partnerships, and defence cooperation cannot be assessed solely by their impact on Indian billionaires or Silicon Valley executives of Indian origin. They must also be measured against their impact on the Indian masses mainly comprising marginalized caste communities who remain excluded from India’s story of economic growth.

Toward a More Honest Dialogue

If Navarro were serious about interrogating the role of Indian upper-caste elites in global trade and politics, he would have focused on those elements within India and the South Asian diaspora and criticised its lobbying apparatus supporting the elite-driven political machinery in India.

But Navarro is not likely to take that step. That responsibility falls instead on scholars, policymakers, and activists who are willing to challenge the popular narratives of Vishwa Guru (World’s Teacher) that surround India’s rise. We must bring caste into the conversation about international relations, recognizing how deeply it structures who gains and who loses in the global politics and world economy.

Conclusion

Navarro’s “Brahmin remark” may have been an offhand jibe, but it reflects a deeper truth: India’s political Economy, International trade and Indo-US relations are shaped not just by geopolitics, but by the social hierarchies that determine who represents India to the world. For too long, these relations have been filtered through an upper-caste elite that monopolizes capital, networks, and legitimacy, both in India and abroad.

If the U.S. seeks a genuine partnership with India—one that lives up to the rhetoric of democracy, equality, and shared prosperity—it must look beyond the elite “Boston Brahmins” of the Indian diaspora and Indian elites. It must engage with the full spectrum of Indian society. Only then, the partnership between the world’s biggest and world’s oldest democracy can truly walk the talk.

Comments