Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: Urgent Lessons for India

- anand kshirsagar

- Sep 12, 2025

- 7 min read

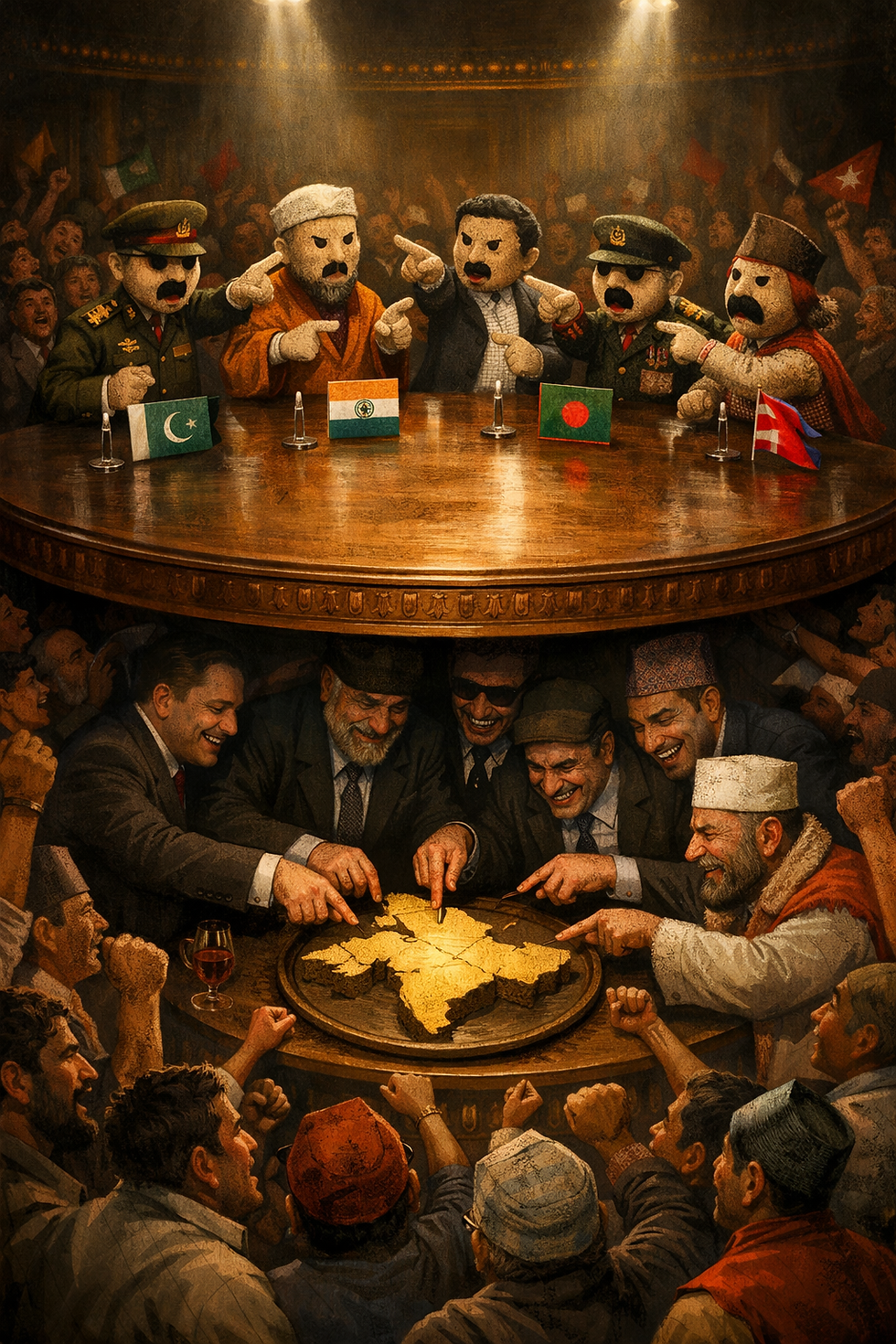

Global South, especially South Asia and Southeast Asia, today is witnessing an unmistakable pattern of political turmoil. From Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, young people and disillusioned citizens are challenging entrenched political elites with a mix of street protests, institutional confrontations, and in some cases, outright violence. These uprisings carry urgent lessons for India—the world’s most populous and youngest democracy—about the risks of elite capture of institutions, social economic inequality, political nepotism and democratic backsliding.

The Wave of Protests Across South Asia and Southeast Asia

Nepal

In Nepal, what began as a protest by “Gen Z” youth against government restrictions on social media sites and displeasure against ‘Nepo Kids’, kids of the Nepalese politicians living lavish lives in foreign lands, erupted into a full-fledged violent anti-government protest. Nepalese students and young professionals, frustrated by unemployment, corruption, and the concentration of political power in the hands of power elites, stormed the parliament, vandalized the prime minister’s residence, and burned down one of the country’s largest media houses. The violence claimed lives, including those of the protestors and that of the ex-prime minister’s wife, when their home was set ablaze. Facing mounting pressure, Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli and several ministers were forced to resign and airlifted to save their lives.

Although these protests may seem to be against the political leaders of Nepal, it is direct popular revolt against the elite upper caste Khas Arya power nexus of Nepal. It is surprising to see the social nature of the political, social, and economic power nexus in Nepalese society. The social-political elites in Nepal have always been the Khas Arya section of Nepalese society, which comprises the upper caste brahmins (Bahun) and Khetri (Warrior caste) from hilly areas of Nepal. From the time of the Nepalese monarchy, to the democratic transition of the nation leading to successive regimes of Nepal Congress or the Nepalese Maoist regime, upper caste Khas Arya political Social elite, maintained their monopolised grip over social, military, bureaucratic, industrial, media, and political apparatus in Nepal.

Although these protests may seem to be against the political leaders of Nepal, it is direct popular revolt against the elite upper caste Khas Arya power nexus of Nepal.

Indonesia

Indonesia has also recently witnessed similarly powerful public demonstrations when the death of the delivery driver, took place at the hands of the police force. Protesters have targeted government buildings, signalling public anger against the elite Indonesian political class, which has failed to address the everyday issues of people like unemployment, housing shortage, mounting inflation, and budget cuts in public services. protesters consider the elite political class to be deeply corrupt and disconnected from citizens’ everyday struggles.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh offers another dramatic example. In 2024–2025, long-serving Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was removed from power following a coup fuelled by widespread discontent. The protests erupted when peaceful demands from university students to abolish quotas in civil service jobs for relatives of veterans from Bangladesh’s war for independence from Pakistan in 1971 were met with heavy-handed repression from Sheikh Hasina’s government. The campaigners had argued the system was discriminatory and needed to be overhauled. More importantly, protestors also highlighted that their long-held grievances consist of unemployment, massive corruption, rising inflation making everyday lives of the Bangladeshi people difficult. Although their request was largely met, the protests soon transformed into a wider anti-government movement. Youth groups, segments of the military, religious organizations, and political opposition all joined forces against Hasina government, ending her decades-long grip on the country.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka too recently went through a massive Aragalaya Protest Movement against its ruling elites, like Gotabaya and Mahinda Rajapaksa. Triggered by higher inflation, unemployment, economic hardships, food shortages, and corruption scandals, demonstrations culminated in the storming of the presidential palace and the forced resignation of top leaders.

The Common Threads of Discontent

These upheavals, though occurring in different national contexts, reveal a shared trajectory of unrest in neighbourhood of India which it cannot afford to ignore.

Several factors unify these diverse uprisings. First and foremost, they are youth-driven movements. South Asian nations are demographically young, with large populations under 35 years old. This generation faces rising unemployment, limited economic opportunities, deeper social and economic inequality, and disillusionment with political institutions captured by entrenched political elites of their nations. Second, these protests are responses to economic inequality and rising hardships in the everyday lives of the common people. Inflation, declining wages, and inadequate access to education and health care are widespread in these nations. At the same time, ownership and access to wealth, land, and capital remain concentrated in the hands of a narrow caste, class, and ethnic elites. This keep the productive capacity of the masses in stagnant condition, making them more excluded from the fruits of market driven neo liberal developmental policies.

Third, opposition to the institutional capture by social and political elites are also recurring themes in all of these protests. A consolidated nexus between Political dynasties, military establishments, bureaucracy, media and business elites dominates the levers of institutional power in these societies, leaving ordinary citizens with little faith in fair governance. Protesters see such democratic institutions not as neutral arbiters but as extensions of nepotic ruling-class interests.

Finally, these movements reflect a deeper popular dissatisfaction with governance models that prioritize elite consolidation of national resources over democratic accountability. When institutions fail to channel the grievances of the common public, the streets become the only remaining arena for popular dissent.

Now, some critics of these political developments in South Asia and Southeast Asia may indicate the possibility of ‘foul play’ of internal vested interests and ‘foreign hands. But one must understand that these public protests at such a massive level cannot simply ‘manufactured’ occur without long-standing public discontent against the power elites and genuine grievances of the public in those societies.

These upheavals, though occurring in different national contexts, reveal a shared trajectory of unrest in neighbourhood of India which it cannot afford to ignore.

India’s Structural Vulnerabilities

India, with its 1.4 billion people, is uniquely exposed to these same risks. Today, more than 60 percent of Indians are under 35 years, making it the youngest large democracy in the world. Yet unemployment remains staggeringly high, and India is among the most unequal nations globally: the top 10 percent own more than 70% of the national wealth, while incomes for the bottom half stagnate.

Despite being a democracy, India’s political and economic power is concentrated in the hands of a narrow elite. Much of this elite belongs to the upper caste section of society that dominates politics, economics, industry, bureaucracy, and media. Social and economic hierarchies exacerbate inequalities between urban and rural populations, and gender disparities further deepen caste and class divides in India. In India’s case, when the nation gained independence from the British colonialism, it enshrined the egalitarian doctrine of social and economic justice to all in its constitution and promised the dignified life to all. But the promises of the Indian democracy are still a long way from its fulfilment. Instead, what we observe today is that the same social, cultural, economic, and political vested interests that once at the forefront of Indian society, are influencing the Indian nation in every sphere of the democratic life.

This structural fragility is compounded by the rise of centralized, majoritarian politics. Since 2014, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the BJP—backed by the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—has promoted an ideology of Hindu nationalism through various policy measures in India. Through the narrative of “Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan”, the government has sought to homogenize India’s cultural and political identity, sidelining linguistic, religious, and regional diversity.

The centralization of power under BJP rule has also coincided with allegations of institutional capture. Today, judiciary, bureaucracy, media, and universities in India have been undermined by political influence. Meanwhile, industrial elites with close ties to ruling political class wield growing political and economic dominance.

Despite being a democracy, India’s political and economic power is concentrated in the hands of a narrow power elites. Much of this elite belongs to the upper caste section of society that dominates politics, economics, industry, bureaucracy, and media.

Rising Signs of Discontent

India has already experienced major nationwide protests in recent years—the anti-CAA and NRC demonstrations, the farmers’ agitation, and growing resistance in non-Hindi-speaking states to Hindi-imposed cultural homogenization by the BJP central government. These movements underscore the vibrancy of anti-incumbent sentiment in India.

However, they also highlight the risks of escalating massive public unrest. If grievances over unemployment, political repression, economic inequality, and cultural imposition are not addressed through democratic channels, they could spill over into the kind of mass demonstrations seen in neighbouring countries. India’s sheer population size that such unrest would have even more destabilizing consequences not only for the nation, but it can turn out to be a regional and global geopolitical crisis.

Eroding Trust in Institutions

Perhaps most troubling is the erosion of public trust in India’s democratic institutions. Recent allegations of electoral fraud and partisan behaviour by the Election Commission of India undermine confidence in the fairness of elections. The mainstream Indian media—dominated by upper-caste, industrial and political interests—often amplifies government’s ideological narratives rather than questioning them.

Even social media, once an alternative space for dissent, is being reshaped by government manipulation. Tactics such as shadow-banning critics, spreading disinformation, and manipulating online information weaken democratic debate in India . The result is intense political polarization, confusion, and a widening gap between citizens and their governments. In such condition, when governments lose touch with genuine public grievances, they risk being blindsided by explosions of public anger.

The Urgent Lesson for India

The turmoil in Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia reveals a stark truth: when institutions are captured by elite nexus, inequality deepens, and youth see no future, government stability comes under grave risk. For India, this lesson is not abstract but immediate. With its youthful population, vast inequalities, and increasingly centralized politics, India mirrors many of the vulnerabilities that have triggered unrest in its neighbouring countries. The way forward for India lies in decentralizing power and resources to ensure equitable regional development, strengthening institutional ownership of political, economic, and social power for historically marginalized communities, restoring the independence and accountability of public institutions such as the judiciary, Election Commission, media, and protecting cultural diversity and free expression against cultural homogenizing pressures. People-centered governance—rooted in social justice, public accountability, and inclusivity—remains the only durable bulwark against such instability. To safeguard its future, India must embrace a politics that is genuinely driven by its people—diverse, democratic, and inclusive.

Comments