Mahatma Jyotiba Phule: The Capitalist Who Dared to Revolutionize India

- anand kshirsagar

- Sep 22, 2025

- 9 min read

When mainstream Indian society imagines the Indian capitalist class, the images that surface are familiar: business families like Tatas, Birlas, Ambanis, Adanis, Mahindras, and Jindals occupy our popular imagination. Today, India’s business elite is drawn almost exclusively from caste communities such as Brahmins, Banias, Marwaris, Jains, Agarwals, Chettiyars, Shroffs, Satodiyas, Parsis, Bohras, and landowning feudal castes who translated their agrarian dominance into industrial power. Even among religious minorities, it is the upper-caste Ashraf Muslims, upper caste Syrian Christians, and Jat Sikhs who are represented as a visible part of the Indian capitalist class among their religious communities.

This dominant image creates a dangerous popular public imagination: that business acumen “runs in the blood” of certain upper-caste groups, while lower caste Bahujan communities are not destined to succeed in entrepreneurship. This is more than an economic myth; it is a social and cultural deficit of imagination, where the Bahujan masses are denied the possibility of envisioning their own presence within India’s capitalist class.

Yet history tells a different story. At the very heart of 19th-century Maharashtra, India lived a man who dismantled this myth with his life and work: Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, not only a pioneering social reformer and educator but also a visionary capitalist and serial entrepreneur.

Roots of Rebellion: Phule’s Caste Background

Jotiba Phule was born in the Mali caste, traditionally associated with floral garland making, which was considered a socially backward caste in the Indian caste system. His experiences of caste-based discrimination shaped his lifelong struggle against Brahminical domination. A pivotal moment in his youth occurred when he was humiliated for participating in the wedding ceremony of a Brahmin friend, as members of the Brahmin community considered it unacceptable for someone from a Shudra (lower caste) to take part in their wedding procession. This incident deeply impacted Phule, sparking his resolve to challenge caste hierarchies and social exclusion.

This personal encounter with exclusion became the seed of a revolutionary philosophy that would later guide both his social reform and his entrepreneurial vision.

Phule as a Serial Entrepreneur Before the Word Existed

Long before the word “entrepreneur” entered India’s vocabulary, Mahatma Phule embodied its essence. He owned and operated multiple businesses across diverse sectors, redefining the relationship between social justice and wealth creation.

Phule established the Poona Commercial and Contracting Company, which built critical infrastructure, including bridges, dams, tunnels, market yards, and railway yards in Pune and the Mumbai region of Maharashtra. He ventured into finance and international trading, becoming one of the first Indians to participate in the booming cotton trade commodities market during the American Civil War. Recognizing the power of financial knowledge, he published a book titled Akhanda, offering guidance to ordinary people on how to participate in the share market, democratizing financial literacy in a way that challenged elite caste monopolies in Indian financial markets.

In the sphere of industry and manufacturing, Phule revolutionized the domestic life of Indians by introducing metal utensils, reducing dependence on fragile clay. He also invested in the media business, ensuring that his ideas and the voice of the Bahujan masses could circulate widely in an era when access to publishing was monopolized by English speaking urban upper castes. On his farm near Hadapsar, Pune city, he introduced modern agricultural techniques like canal irrigation and demonstrated its effectiveness to sceptical farmers who believed crops could only survive on rainwater.

Capitalism With a Social Conscience

The social and economic tendency of upper caste Indian capitalism is to become an active custodian of the caste-based and patriarchal status quo, reproducing inequality across generations. Far from challenging the Brahminical social order, the upper-caste capitalist elite consistently acted as its ally—using cultural authority, political influence, economic dominance, and religious legitimacy to consolidate power. In this framework, the Bahujan masses remained confined to the roles of laborers, producers, and consumers, sustaining a system that excluded them from meaningful participation in wealth creation. The Brahmin-Baniya capitalist order foreclosed the radical possibilities of reimagining social, cultural, and economic relations, making the example of Mahatma Phule even more vital today.

Unlike the Brahmin-Baniya capitalist nexus, which historically allied with the caste system to preserve hierarchy, Phule’s capitalism was radical in its social imagination. He reinvested his surplus not in hoarding wealth but in fundamental social transformation. The schools he founded for girls, the shelter homes he established for widows, abandoned women, and their children represented a model of reinvestment in human capital with empathy and radical acceptance of women's empowerment.

Mahatma Phule also played a crucial role in developing the labour movement in India. Narayan Meghaji Lokhande, a close associate of Mahatma Jotirao Phule, played a leading role in engaging with Bombay’s textile workers. Phule, together with his peers Lokhande and Bhalekar, addressed workers’ gatherings and highlighted their struggles. Notably, before their efforts to organize peasants and laborers, no group or institution had attempted to address the concerns of these communities. With Lokhande’s support, Phule went on to establish India’s first workers’ organization, the Bombay Mill Hands Association.

The unique identity of Phule’s revolutionary capitalism, was its proactive promotion of labour unionisation and empowerment of socially marginalised Bahujan labor class. Even today, this radical reimagination of capitalism is still an anathema for many capitalists in India.

Phule understood that true economic empowerment could never be separated from cultural and political liberation. His wife, Savitribai Phule, stood as his equal partner in this mission, pioneering women’s education, self-reliance, and empowerment. Together, they redefined both the purpose and ethics of wealth creation in a deeply unequal society—demonstrating that capital, when liberated from the exploitation of caste and patriarchy, could serve as a transformative force for social liberation.

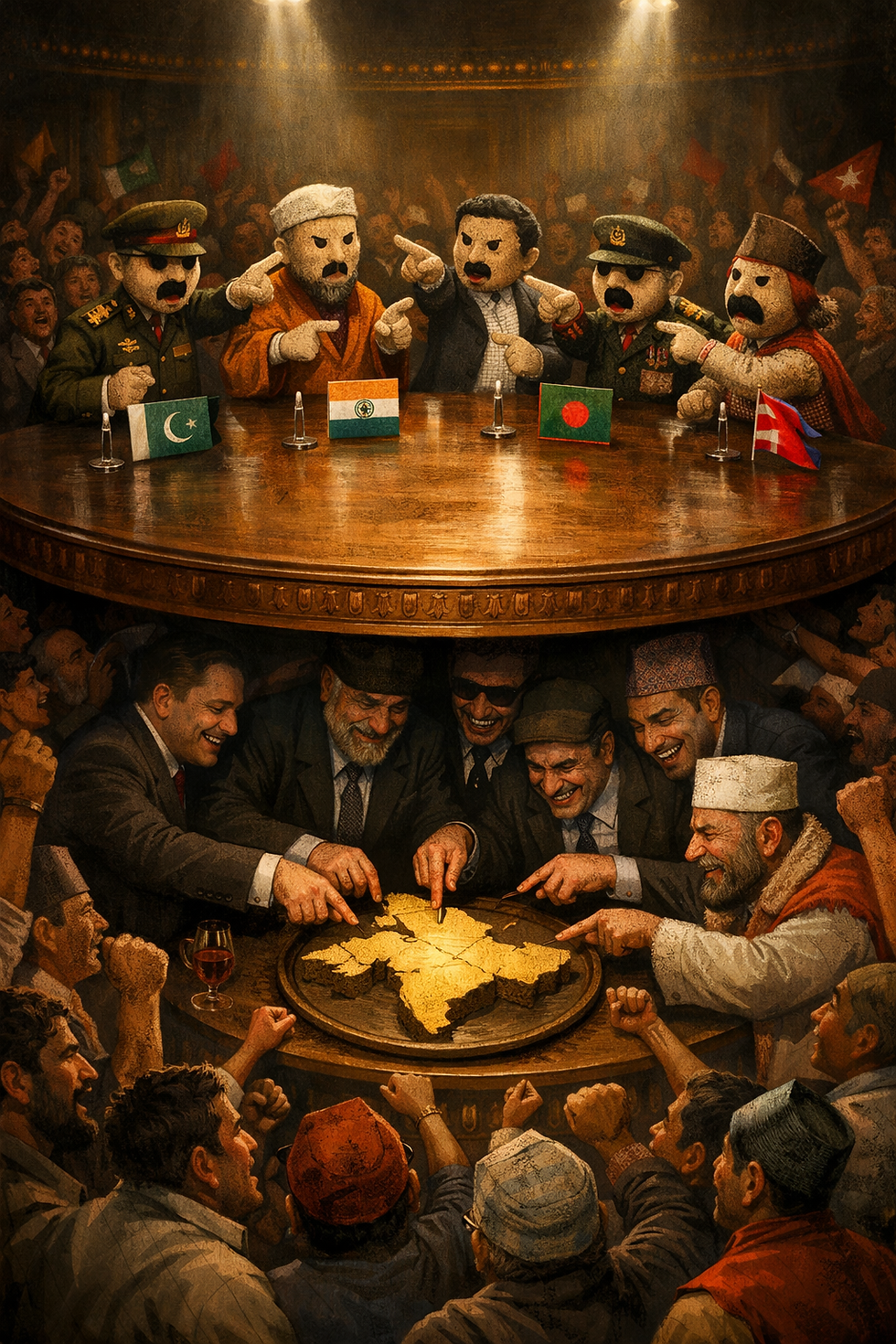

The Shetji-Bhatji Nexus vs. Phule’s Radical Socially Conscious Entrepreneurial Model

Way before economists and philosophers like Amartya Sen, Martha Nussbaum put forward their capabilities approach and human development approach, Mahatma Phule theorised the root cause of the social, economic, and political degradation of the lower caste masses of Indian society in educational degradation of the Shudra/lower caste masses. He theorised-

As a capitalist revolutionary and bold social reformer, his understanding of the root cause of material and social degradation of the bahujan masses was an original intellectual contribution and provided the strong philosophical, social, political, economic, and educational foundations for the next generations of thought leaders.

Phule coined the term Shetji-Bhatji to describe the exploitative alliance between merchants and the Brahmin priest class, a nexus that extracted Bahujan labor while consolidating both economic and cultural power. His entrepreneurial vision was the antithesis of this model. For Phule, wealth was not an instrument of domination but a tool of liberation. He recognized that capital, when rooted in justice and equality, could dismantle rather than reinforce social hierarchies. His enterprises became collective projects to uplift marginalized communities and redistribute opportunity, rather than isolated ventures of personal gain.

Mahatma Jyotiba Phule was not only a social reformer and entrepreneur but also a radical intellectual whose writings and actions challenged the very foundations of caste and colonial capitalist domination.

He authored his seminal work, Gulamgiri (Slavery), where he decoded the social and economic exploitative nature of the Brahminical caste system, dedicating it to the Black and White soldiers of the American Civil War who fought to emancipate enslaved black people from the clutches of white plantation capitalism of the American South. In a striking act of protest against British colonialism, Phule appeared before the Duke and Duchess of Connaught in 1888 dressed as a poor Indian peasant, defying Victorian decorum to highlight the plight of farmers and the devastating effects of famine and exploitation of upper caste money lenders on farmers of the Deccan region of India. His Marathi text Shetkaryacha Asud (Cultivators’ Whipcord) offered a searing critique of peasant exploitation, while his play Tritiya Ratna exposed the hypocrisies of caste and patriarchy. Phule’s own example revealed that Bahujan capitalism did not have to replicate the Brahmin-Baniya model of hoarding wealth by being complicit in caste based economic inequality and perpetuating exploitation of the Bahujan masses. Instead, he articulated and practiced a revolutionary form of capitalism rooted in the holistic transformation of the oppressed masses. His entrepreneurial surplus was reinvested in the fundamental social transformation of education, social empowerment, and public welfare—unlike today’s corporate social responsibility or philanthropy, which often stems from superficial attempts of charity, benevolence, and developing political influence and cultivating public legitimacy for their business rather than fundamental systemic social change. Phule even supported the Indian nationalist movement, contributing funds to secure the bail of arrested Indian Nationalist Congress leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak, though his own vision of Indian liberation was broader and more radical than Tilak's. For Mahatma Phule, capitalism was never just a private, isolated pursuit of profit; it was inseparable from the larger struggle against caste oppression, patriarchy, and colonial capitalism. He demonstrated that wealth and enterprise, when embedded in public service, could become tools of emancipation rather than social domination. His life and work thus stand as a rare global example of revolutionary capitalism that directly challenged entrenched systems of power instead of collaborating with them.

Challenging Patriarchy and Caste Through Enterprise

The social, cultural, economic, and political foundations of the upper-caste capitalist class were deeply rooted in caste relations, where intergenerational wealth and access to networks of power were sustained by the strict enforcement of caste endogamy and the control of women’s sexual choices and bodily autonomy. In caste-driven societies such as India and the broader South Asian region, ownership of capital and property was thus inseparable from patriarchal social, economic, familial, and legal structures.

In direct opposition to this model, Phule’s capitalism was not only anti-caste but also radically feminist. He and his wife, Savitribai Phule, advanced women’s education, defended women’s right to autonomy over marriage and reproduction, and fought against oppressive practices like the enforced shaving of widows’ heads—even mobilizing barbers to strike against this degrading ritual in a striking act that merged labor organizing with feminist social reform. Unlike upper-caste capitalists who maintained patriarchal control to preserve their caste and class order, Phule envisioned a model where women’s agency and equality were central to social and economic progress. His capitalism was therefore revolutionary not only for its inclusivity but also for its insistence on social and economic empowerment of women.

The Revolutionary Potential of Bahujan Capitalism

Phule’s example shatters the fatalism that Bahujan communities “cannot succeed in business.” His life proves that Indian capitalist enterprise need not be synonymous with exploitation, hierarchy, or exclusion of the Bahujan masses. Instead, Bahujan capitalism could be built on principles of justice, equality, and collective transformation.

By tying economic enterprise and social reforms to the avenues of education, agricultural reform, and social justice causes, Phule demonstrated that capitalism could serve as an instrument of empowerment for those historically excluded from wealth creation.

Jyotiba Phule's capitalist model offers an alternative genealogy of capitalism—one that challenges the monopoly of upper-caste elites and expands the horizons of who can be imagined as part of India’s capitalist class.

Phule’s Lasting Impact: A Foundation for India’s Progress

Mahatma Jyotiba Phule’s life’s work laid the groundwork for a profound social awakening across India, particularly in Maharashtra, by unleashing a powerful social, political, economic, and cultural consciousness. This momentum led to the development of mass movements and institutions dedicated to public education, significant strides toward gender equality and a rise in female workforce participation, strong advocacy for the laborers and farmers' rights, and a vast expansion of cooperative institutions in rural parts of Maharashtra. This foundational progress, in turn, catalyzed an era of remarkable economic growth, supporting the rise of private industrial capitalism in cities and the sugar and milk cooperatives movement in rural Maharashtra. This dual development played a crucial role in transforming Mumbai into India’s modern financial capital and established Maharashtra as a primary engine of India’s economy—a status reflected in the state’s continued position as one of the largest contributors to the national treasury.

Ultimately, Phule’s model offers a radical alternative vision of capitalism—one that challenges the monopoly of traditional, exploitative upper-caste elite control and boldly expands our imagination of who can be a business leader and wealth creator in India.

His legacy endures as a powerful testament to the idea that capitalism can and should serve the people, rather than the other way around.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Phule for Today

In contemporary India, where corporate power is dominated by Brahmin-Baniya conglomerates and philanthropy is framed within neoliberal corporate logic of self-interest, Mahatma Phule offers us a forgotten but urgent lesson. He was not merely a social reformer or educator but a bold entrepreneur who used enterprise as an agent of economic empowerment against social ills like caste capital exploitation and patriarchal social relations in India. Phule’s life invites us to reimagine capitalism itself—not as a machine of exploitation but as a tool of liberation when wielded by the oppressed. His radical, revolutionary model of Bahujan capitalism remains a powerful alternative history of Indian Capitalism, one that India urgently needs to reclaim to break the stranglehold of caste on its stale economic imagination.

Comments