How Delimitation Shapes Caste-Based Politics in India

- anand kshirsagar

- Aug 17, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

Introduction

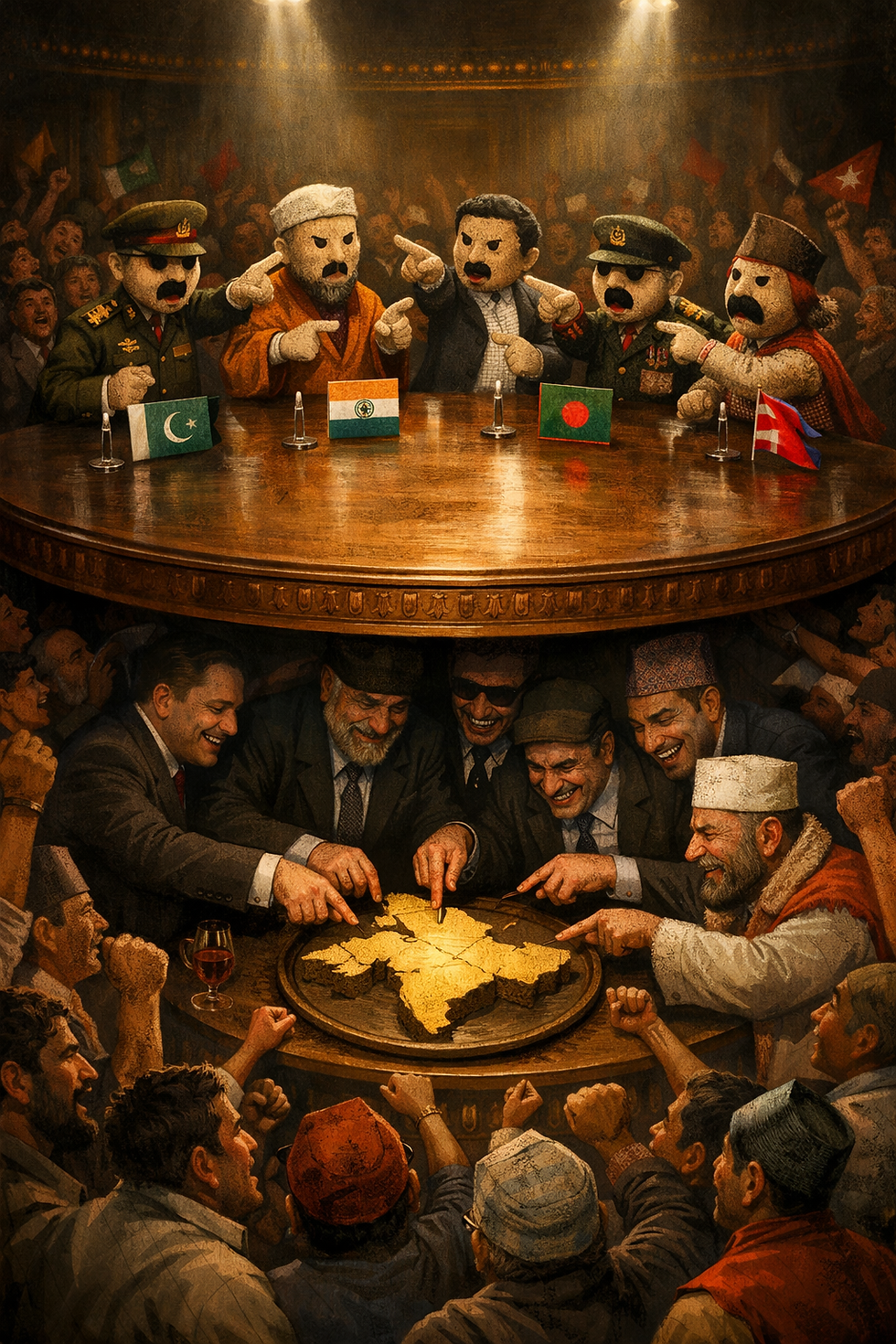

Delimitation, the process of redrawing the boundaries of electoral constituencies to reflect demographic changes, is one of the most consequential yet under-discussed aspects of Indian democracy. At first glance, it appears to be a technical, administrative exercise aimed at ensuring fair representation. But in a society structured by caste, where political mobilization and voting patterns often follow caste-based lines, delimitation has profound consequences for the distribution of political power. The timing, methods, and outcomes of delimitation exercises intersect directly with the dynamics of caste representation, political party strategies, and the balance between historically dominant groups and historically marginalized communities.

The Constitutional Basis and History of Delimitation

India’s Constitution mandates periodic delimitation to keep constituencies aligned with changes in population. The Delimitation Commission, an independent body, is tasked with carrying this out. Since independence, India has had four major delimitation exercises: in 1952, 1963, 1973, and 2002. However, after the 1971 Census, delimitation was frozen until after the 2001 Census to encourage population control. This freeze, later extended until 2026, created a tension: states in the Hindi heartland with higher population growth saw their political weight reduced compared to southern states with slower growth.

While the freeze was justified in terms of balancing regional interests, it also delayed debates about representation in terms of caste demographics. With the rise of Mandal politics after the 1990s, caste identity became central to political competition, yet constituency boundaries continued to reflect an earlier demographic reality.

Delimitation and the Question of Reserved Constituencies

One of the most direct ways delimitation affects caste politics is through the reservation of constituencies for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). Article 330 of the Constitution ensures proportional representation for SCs and STs in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies. During each delimitation, constituencies are reallocated to reflect the SC/ST population as per the latest Census.

This reallocation has major political consequences. A constituency that was once dominated by Other Backward Classes (OBCs) or upper castes might suddenly be reserved for SCs, altering the strategies of political parties and the career trajectories of established leaders. For marginalized groups, reservation ensures entry into legislatures, but delimitation also means their strongholds can be dismantled or shifted, weakening long-term political consolidation. For instance, Dalit leaders often find themselves displaced from their constituencies after reservation patterns change, forcing them to rebuild political bases elsewhere.

OBCs, Delimitation, and the Mandal Era

Unlike SCs and STs, OBCs do not enjoy reserved constituencies in Parliament or state assemblies. Their political power has instead grown through numerical strength and party mobilization, particularly after the implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations in 1990. Delimitation affects OBC representation indirectly: by reshaping the caste composition of constituencies, it can dilute or strengthen OBC dominance.

For example, a constituency where Yadavs, Kurmis, or Jats hold decisive sway may be merged with neighboring areas where their numbers are smaller, thereby reducing their bargaining power. Conversely, redrawing boundaries may also consolidate OBC concentrations, enabling parties like the Samajwadi Party (SP), Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), or Janata Dal (United) to translate caste arithmetic into electoral victories. Thus, delimitation is a hidden lever in the broader Mandal vs. Kamandal battle that defines much of North Indian politics.

The Freeze and the North-South Debate

The decision to freeze delimitation until after 2026 was framed as a question of fairness between states that succeeded in controlling population growth and those that did not. Southern states, where fertility rates declined earlier, feared losing representation in Parliament if delimitation proceeded based strictly on population. However, beneath this regional debate lies a caste dimension.

Southern politics has been shaped by powerful anti-caste movements and strong OBC/Dalit mobilization, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. By contrast, northern states with higher fertility rates—Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan—remain deeply structured by caste hierarchies, with dominant castes such as Yadavs, Kurmis, Jats, and upper castes retaining significant influence. Post-2026 delimitation is likely to enhance the political weight of these Hindi heartland states, effectively strengthening the role of caste-driven politics at the national level.

This shift could dilute the influence of southern states that have historically produced more inclusive welfare models and caste-based social justice policies. In other words, delimitation has the potential to reshape not only regional power balances but also the trajectory of caste politics at the national level.

The BJP, Delimitation, and Caste Coalitions

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has approached delimitation with a keen awareness of its caste implications. The party’s success over the last decade has rested on its ability to consolidate upper-caste voters with non-dominant OBCs and Dalits, thereby breaking the monopoly of Mandal-era parties. Delimitation, especially after 2026, could further consolidate this strategy.

By increasing the number of seats in northern states where caste identities remain politically salient, the BJP can continue to mobilize caste coalitions under a Hindutva umbrella. At the same time, delimitation may weaken parties like the DMK or Left in the south, which rely heavily on caste-conscious welfare and representation politics. Thus, delimitation could indirectly support a pan-Hindu consolidation that diminishes the potency of caste as a mobilizing category—though in reality, caste arithmetic would remain central to the BJP’s calculations.

Challenges for Dalit and Bahujan Politics

For Dalit and Bahujan parties like the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), delimitation presents a double-edged sword. On the one hand, reserved constituencies guarantee Dalit representation, keeping the Bahujan presence in legislatures alive. On the other hand, shifting reservations disrupt established Dalit strongholds, preventing the long-term institutionalization of Dalit power in particular regions.

Moreover, since OBCs lack formal reservation in electoral politics, their dominance often overshadows Dalit representatives in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Delimitation that consolidates OBC-heavy constituencies could further marginalize Dalit-led parties, forcing them into alliances where their autonomy is compromised.

Looking Ahead: Delimitation after 2026

The next delimitation, expected after the 2031 Census, will be a watershed moment. With population growth uneven across caste groups and regions, redrawing constituencies will inevitably reshape caste-based political strategies. States like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, with larger populations and strong caste-based mobilization, are likely to gain seats, while states like Kerala or Tamil Nadu may see their influence shrink.

This could intensify caste competition in the Hindi belt, where every redrawn boundary recalibrates the balance between Yadavs, Kurmis, Dalits, and upper castes. At the same time, the weakening of southern states may undercut the progressive anti-caste politics pioneered by Dravidian and Ambedkarite movements. Delimitation will not erase caste; it will reconfigure how caste translates into electoral arithmetic.

Conclusion

Delimitation is not a neutral technical exercise; it is a deeply political process with direct implications for caste-based politics in India. By altering the caste composition of constituencies, reallocating reserved seats, and shifting the regional balance of power, delimitation influences who gets represented, whose voices are amplified, and whose interests are sidelined.

As India approaches the 2026 deadline, debates on delimitation must go beyond regional fairness and population control. They must also grapple with questions of caste equity, representation, and the need to balance numerical strength with historical marginalization. For a democracy built on the promise of equality, delimitation is not just about drawing boundaries—it is about redrawing the social contract between caste, politics, and representation in India.

Comments